by admin | May 28, 2017 | Authenticity, character, crime fiction, Cumbria, fact-based fiction, Fallout, plotting, readers, Unbound, Uncategorized, Windscale fire

Three years ago I was in the final stages of writing my third novel ‘Fallout‘, which had as its backdrop the nuclear reactor accident at Windscale in Cumbria in October 1957.

Deciding on that context for a story about finding love in later life was a gamble. For a start, the background might end up being much more interesting than the main story line. And dealing with a real event was always going to be tricky. It’s a touchy subject here in Cumbria even after sixty years: the final report on the incident used a phrase about ‘local errors of judgement’ that still rankles. (Actually the phrase was inserted into the report by the Macmillan government as a way of explaining the incident to the Americans without blaming the government’s own rushed reactor building programme.) And of course, because it was a ‘real’ incident within living memory it was essential for me – a local ‘offcomer’ – to get the facts right.

The inside story of the reactor fire was a complicated technical issue. How was I going to help the non-scientific reader to understand what was really going on, and why the key the decisions were made? The plan was to place a character on the inside of the Windscale whose job was to ask questions about the operation of the reactor. This character would act as the reader’s ‘friend’, gathering information in an intelligible way. in ‘Fallout’ this character was Lawrence Finer, seconded to Windscale from Harwell, the nuclear research facility near Oxford.

In my next book ‘Burning Secret’ I face the same issue – explaining farming to a non-farming readership, and then clarifying the complications of a catastrophic infection that decimated our farm animals in 2001. I need a character that acts as the ‘guide’ to a specialist subject for a non-specialist audience. Talking to a local dairy farmer last week it occurred to me how to handle this.  Large dairy farms often employ people to help with milking and the care of the herd, but during the outbreak restrictions were introduced that made it impossible for dairy farm workers to work normally, going home after work and coming back the next day. This particular farm asked a family friend from Liverpool to come and stay on the farm for the duration to help them, and the young man had no experience of farming life. He reacted to the everyday routines of the farm as you or I might, noticing things that the farmers took for granted, asking naive questions, making mistakes through lack of experience. In literary terms, this character’s function is somewhere between the Greek chorus and the gravediggers in Hamlet, and more emotionally detached than the farmers themselves as the outbreak spread ever closer. In a crime story, as this will be, the ‘stranger’ can also be a useful source of tension and mystery. Let’s see how it all turns out.

Large dairy farms often employ people to help with milking and the care of the herd, but during the outbreak restrictions were introduced that made it impossible for dairy farm workers to work normally, going home after work and coming back the next day. This particular farm asked a family friend from Liverpool to come and stay on the farm for the duration to help them, and the young man had no experience of farming life. He reacted to the everyday routines of the farm as you or I might, noticing things that the farmers took for granted, asking naive questions, making mistakes through lack of experience. In literary terms, this character’s function is somewhere between the Greek chorus and the gravediggers in Hamlet, and more emotionally detached than the farmers themselves as the outbreak spread ever closer. In a crime story, as this will be, the ‘stranger’ can also be a useful source of tension and mystery. Let’s see how it all turns out.

by admin | Aug 2, 2016 | cover, Fallout, Publishing, title, Uncategorized, Windscale fire

There’s no copyright on book titles. I didn’t realise that to start with and fretted that I couldn’t ever use a title that had been used before, but I can, although it’s still needs thinking about.

The easiest way to check is to do what I did yesterday – draw up a shortlist and then look each title up on the Amazon data base. I know it’s lazy, but it’s quick. Looking carefully at what comes up helps me to decide whether a previously used title could be used again. If the title has been used before, which almost all titles have, I look for various criteria:

- Was the previous book the same genre? I want a title for my novel: if the previous title was for non-fiction, it’s unlikely that someone looking it up would be confused.

- Has the title been used in the UK, or just in North America or elsewhere around the world? If it’s just in the US, for example, I wouldn’t hesitate to use the title again.

- Was the title previously used for a paperback, or just for an ebook? I publish in both formats, and I might still choose to use the title again, although I might slip down the priority order

- How long ago was the title I want used previously

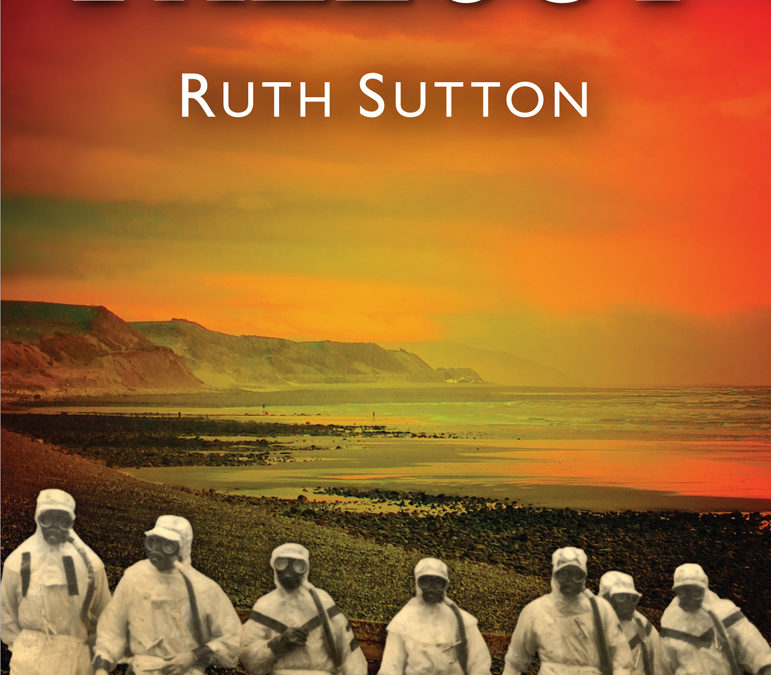

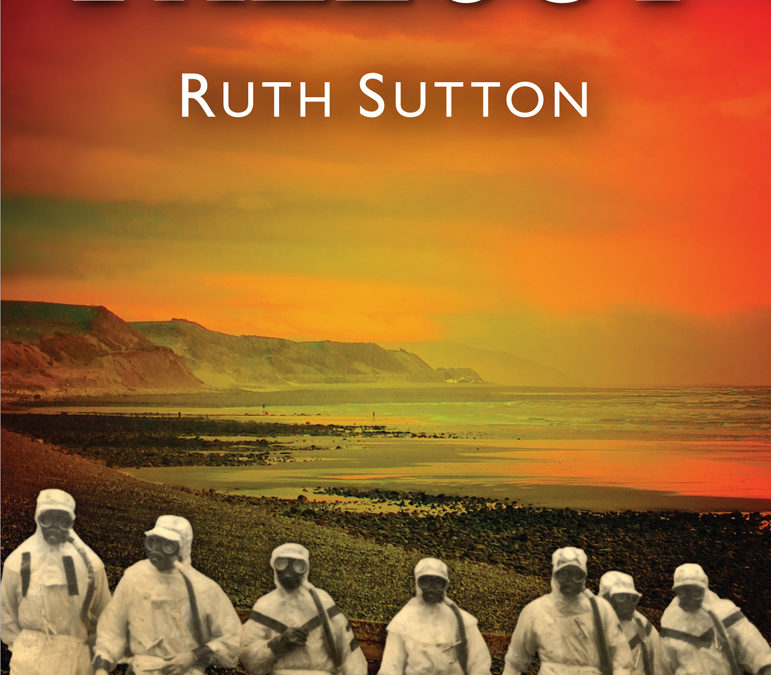

? If it’s within the past year or two, that could be a problem. In 2014, when I was looking for a title for my novel set in and around the Windscale reactor fire in Cumbria in 1957, the title ‘Fallout’ was an obvious choice, and I really wanted it. Just three months before we went to print another novel appeared with that title, published in the UK, and I had to make the choice. In the end I decided to go ahead, but I’ve noticed that since publication we’ve had two copies returned – which I guess arose from the confusion over the title. I still think I made the right decision, though, and the cover is pretty special too. ‘Garish’ someone called it, but at least it gets noticed.

? If it’s within the past year or two, that could be a problem. In 2014, when I was looking for a title for my novel set in and around the Windscale reactor fire in Cumbria in 1957, the title ‘Fallout’ was an obvious choice, and I really wanted it. Just three months before we went to print another novel appeared with that title, published in the UK, and I had to make the choice. In the end I decided to go ahead, but I’ve noticed that since publication we’ve had two copies returned – which I guess arose from the confusion over the title. I still think I made the right decision, though, and the cover is pretty special too. ‘Garish’ someone called it, but at least it gets noticed.

When I’ve checked all these criteria, I find that some titles don’t feel so appealing, as they have been used before many times, and quite recently. The exercise yesterday brought the list of eight possible titles down to two or three, which was helpful. Once my trusty editor returns from her hols the fateful decision will be made and possible covers will then be designed. Still on schedule for publication in November 2016.

by admin | Mar 13, 2016 | Authenticity, ethical questions, fact-based fiction, Fallout, genre, historical fiction, research, Sellafield, Uncategorized, West Cumbria, Windscale fire

At the Words by the Water festival in Keswick last week, we were able to witness two versions of the same real events and thereby to compare them. The events in question concerned the life and work of Alan Turing, the mathematical genius whose work enabled the German ‘enigma’ code to be cracked during World War 2. The first presentation came from Turing’s nephew Dermot Turing who gave us five ‘myths’ about his uncle and proceeded to use his detailed knowledge of the family and the history to replace these myths with something closer to the truth. His talk was followed by a showing of ‘The Imitation Game’ a 2014 film ostensibly about Turing’s life and war work, and the events leading up to Turing’s death by suicide in 1954.

At the end of his talk, Dermot Turing urged us to enjoy the film we were about to see, but warned us that the Alan Turing we were going to see portrayed was not, perhaps, the real man, but a filmic construct. He didn’t use those words: in fact he was very polite about a film that demonstrated each of the five myths that he had previously been at pains to deconstruct. No point in railing against it, I suppose, although I doubt whether my reaction would have been so measured.

The film was much heralded when it was released. I can’t recall all the fulsome epithets used by the critics, but some of them at least thought it was very good. But did it actually tell the story accurately? No. In some crucial respects, the needs of the film, the demands of the genre and the presumed expectations of the audience clearly over-rode any semblance of historical accuracy. One example: Turing was already working on the German code before the war began and had cracked it by 1941, but in the film the breakthrough is beset by technical and political difficulties and wasn’t achieved until much later in the war, as the need for it became ever more urgent, creating a false tension that never actually happened.

The script – in my view – was dire, cliche-ridden and sentimentalised. I checked later: the scriptwriter was American and born in 1981. To what extent, I wondered, were both the script and the unfolding of the story affected by the demands of the 3 act structure so beloved of film-makers: – the ersatz crises, the bullying army officer, the cynical MI6 man, the fresh-faced young man who had by some fluke turned up in the code-breaking team. And then there was Keira Knightley as the only woman on the team. Words fail me. Why her, again? I assume I was expected to suspend my disbelief for the sake of the story, but instead I was increasingly irritated by the whole sorry mess.

On the way out I began thinking about my own attempts to weave real events into a fictional setting, and whether I too should be castigated for sacrificing authenticity in pursuit of a good tale. The issue is most pronounced in the third book of my West Cumbrian trilogy ‘Fallout’, which is set against the backdrop of the nuclear reactor fire at Windscale in October 1957. I had 90,000 words rather than an two hour film script to play with, but still the responsibility to portray the real events as accurately as I could weighed heavily on me, for two reasons. First, it was a point of pride that I got my facts right. And second, Windscale is just a few miles up the coast from where I live and the fire happened not that long ago, within my memory and those of many people who live around me in this area. You can’t, and shouldn’t, muck about with the known facts when many of them are known by so many. My research was careful and meticulous. Even if it made a better story I couldn’t make the fire last longer, or less long, or do more damage, or require intervention beyond the means of the local men who managed to get it under control. So why did the makers of ‘The Imitation Game’ claim to use a real story, take such liberties with it, and get away with it? I can be very critical of my own attempt to blend fact and fiction but at least I tried to respect the events rather than abuse them.

Historical fiction that purports to represent real events raises particular challenges when those events are within living memory. It’s something I’d like to think more about as a writer, and try not to imitate ‘The Imitation Game’.

by admin | Feb 6, 2016 | A Good Liar, Authenticity, Cruel Tide, fact-based fiction, Fallout, Forgiven, historical fiction, research, Windscale fire

I’m doing an online crime writing course with the Professional Writers’ Academy, and Week Three is devoted to ‘research’. This is not the first thinking I’ve done about it: you can’t write a family saga based in a specific place (West Cumbria), and a specific time (the first half of the twentieth century), without spending a daunting amount of time digging for details, followed by even more time deciding how little of that detail is actually needed. What I’m beginning to understand are the various layers and type of research to be undertaken, and when’s the best time to do it. The first duty of a writer after all is to write, and you have to make sure that research doesn’t become a distraction from the writing rather than a necessary preparation for it.

As soon as I’ve decided on the ‘setting’, both time and place, I’ll start researching the first layer of information. It could be about the geography of the area, using maps and visits, just to get the lie of the land, literally. Or it could be combing through the newspapers for the given time, looking for the details of lives lived at the time and the background events. In 1969 the first people walked on the moon, and the provisional IRA was formed, both of which might be in the minds of my characters at that time, or have a bearing on the plot. The original germ of an idea for a story can be helped by this immersion in the times, and some details or incidents jump out at you. Many things may find their way into your notebook, but only a few really stick in the mind. I recall the court case reported during rationing in 1947, where it was explained that an illegal ham hanging in someone’s attic was discovered when a mouse ate through the string and the ham crashed through the ceiling into someone’s bedroom. That found its way into my second novel ‘Forgiven’. In the third one ‘Fallout’ I’m inside the nuclear plant at Windscale ten years later and learn that one of the essential maintenance procedures for the reactor required someone to hold down a button with their finger for long periods of time, until the finger hurt. Who knew? It showed just how troublesome the care of the old reactor had become.

You have to know when to stop ‘reading around’, or the fascination of what you discover can absorb too much of the energy that should now be devoted to the next stage, getting on with the development of the plot and the characters, and on into the first draft. When you get writing, you quickly discover the gaps in the research that will need to be filled, and the list of specific questions mount. What model of motorbike would someone buy in 1947? What were police radios like in 1969? What would be on the juke box in the cafe in 1970? When and why was the decision made to turn off the fans in the burning reactor?

A remarkable number of these questions can be answered without ever leaving the house, if you’re prepared to pick away online until the answer is found. Even better, you can sometimes discover the gold seam of authentic first hand ‘primary’ information, such as the transcription of the accident enquiry about the William pit explosion of August 1947 that was part of the backdrop of ‘Forgiven’. Or the 1985 Hughes Report on the Kincora Boys’ Home scandal in Belfast that provided much of the background of institutional child abuse that I used in ‘Cruel Tide’.

But some of the best information is uncovered when you talk to people. They give you snippets that you would never find elsewhere and add valuable authenticity to your story. I heard from an ex-policeman that he refused to drive a Panda car on his rounds when they came into use because it would have meant swapping his helmet for a flat cap, and he wouldn’t do it. The daughter of a woman who’d sorted coal in the screen shed at a local pit told me that the screen lasses had to wear gloves whenever they went out to cover their scarred hands that no amount of scrubbing could properly clean. Hard work, and hard times, before the process was mechanised and the screen lasses passed into history.

I learned the hard way that much of this wonderful detail can slow your story down and has to be sacrificed to ‘pace’. In the first novel ‘A Good Liar’ great swathes of background detail about a minor character’s clothes and shoes was cut out, and some of looping ‘side-stories’ needed to go as well: however interesting, they were a distraction and inessential to the main thrust of the action. They had to go, however much it grieved me.

Maybe I’ve made this rod for my own back. It might be less onerous, and authentic detail more straight-forward, if I chose contemporary settings. Historical settings make the writing life harder, with more hours necessarily devoted to gathering and checking the detail. But I still think that such a setting lengthens the shelf-life of the book, which matters a great deal to a self-published author whose promotion and sales have to be spread over a longer time frame than the commercial publishers. So long as I keep writing and publishing, my previous books will keep selling as they are already set in the past and cannot therefore age.

by admin | Jan 9, 2016 | Authenticity, Explicit details, fact-based fiction, Fallout, Forgiven, historical fiction, landscape, plotting, research, stories, Uncategorized, Windscale fire

I’m sure anyone who writes a novel is asked the question: ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ I can’t speak for anyone else, but thinking back on the books I’ve written so far, there seem to be a few places where plot ideas come from.

- My own experience, things that have happened to me personally, together with all the emotions that surrounded them. Some of these are from decades ago, others more recent. I’m not providing any examples of these, to preserve my own privacy and the trust of those around me.

- Stories or snippets of stories I’ve heard from other people. One of these, told to me many years ago, concerned growing up in Belfast in the 1960s with a Catholic father and protestant mother. Another, just a memorable snippet, was about a young man whose wife left him and then returned to their house a few days later while he was at work and removed every stick of furniture, every carpet, curtain and light fitting. He was too shocked and humiliated to track her down.

- Details gleaned from contemporary newspapers and accounts. I use the Whitehaven News for some of this background colour, peering at the microfilm reader to find authentic details that could later become small valuable nuggets in the story. It’s a useful source as it’s weekly and contains all the court cases, petty theft, accidents, and features that add depth to the picture I’m painting. The post-war period I researched for ‘Forgiven’ was rich in detail that evoked that particular time: the parish council resolution that refused to celebrate the anniversary of VE Day in 1946 as they had ‘nothing to celebrate and nothing to celebrate with’; the couple who were caught handling blackmarket pork when a mouse ate through the string supporting a heavy illegal ham hanging upstairs, with damaging consequences. In ‘Sellafield Stories’ an oral history of the Cumbrian nuclear plant I found some rich detail about the reactor fire of October 1957 from people who were there at the time. Transcripts of hearings and enquiries are also great ‘primary sources’, raw, unfiltered by anything except the capacity of the note-taker to capture everything that was said. One of the survivors of the William Pit disaster of August 1947 gave evidence to the official enquiry about his experience of the explosion and his escape from the mine, and I took some of his words directly into my text for ‘Forgiven’. Maybe it’s the historian in me that get so excited about the authenticity of evidence like that.

- Places, and what might have happened, or could happen in this setting. When I did the walk across Morecambe Bay from Arnside a year or two ago I was very struck by the care we had to use when approaching the shore at Kents Bank to avoid a shiny grey patch of mud that wobbled visibly as we came close. This was quicksand, and a false step into it could have been life-threatening. My latest novel ‘Cruel Tide’ drew its opening scene from this experience.

None of these nuggets, of themselves, provide you with a plot, but some of them will provoke the essential ‘what if?’ questions from which great stories can be created. They also remind you of features of earlier times that could provide a starting point. For the novel I’m researching at present, a casual meander around some websites has already provided a striking image that will anchor the plot at the start and leave an after-taste of menace and threat. I had to decide who would witness this image, where, when and how, and what impact it might have, and the story began to take shape. It’s very early days yet, but I’m pretty sure that I already have the first chapter. Once I get to that stage, the story ideas begin to bubble up, adding more strands and twists. The trick is to know when to stop adding layer after layer of complexity and characters, how to shape the story into the necessary peaks and troughs, and then take a deep breath and start….’Chapter One’.

by admin | Aug 23, 2015 | cover, Cumbria, fact-based fiction, Fallout, Forgiven, historical fiction, Lake District, promotion, readers, self-publishing, Windscale fire

Last weekend I went to Gosforth Show, my first and possibly my only local show of the season. The summer months here in Cumbria are stuffed with shows: from July to September there’s one every Saturday and Sunday, and sometimes mid-week as well. Some are small, some massive. The biggest ones are generally in the more populous and popular areas of the Lake District, taking advantage of the influx of visitors at this time of the year. The formula is always much the same: local farmers and gardeners present their offerings in a large number of ‘classes’. It could be ‘best Herdwick tup’ (ram), or best calf, or leeks, or sweet peas, or even strawberry jam or Victoria sponge cake. Competition is fierce and the winners are impressive. And of course there are ‘attractions’ such as the ‘monster trucks’ at Gosforth Show this year, which apparently cost a fortune but may have contributed to the biggest numbers ever attending the show. I managed not to see them, but from my spot in the Local History tent the noise was deafening. During the display women of my age came to visit me, asking ‘Why does anyone want to watch those ghastly things?’, to which I had no adequate response.

Despite the noisy mysteries of the monster trucks, I had a great time, so good in fact that I didn’t have a chance to see the rest of the show beyond the Local History tent until I carried my stuff to the car at the end of the day, just as the Grand Parade of all the animal winners was processing round the ring. What did I do all day, you might ask. Well, I stood in front of the home-made display explaining and illustrating my novels, talked to people who passed by, and sold a heap of books as well. There were some great conversations, about the settings of my trilogy, which book readers preferred, and why, and the local events that form the background of the plots. A couple stopped by, and the man stared at the cover of the third book ‘Fallout’, which depicts some of the men who went to fight the fire in the nuclear reactor at Windscale in 1957, wearing their protective suits and helmets. He pointed at one of the men in the line. ‘That’s my Dad,’ he said. I was thrilled to have found such a close connection to this iconic event in Cumbria’s history. He was thrilled to see his Dad on the front cover of a book, albeit unrecognisable in his anti-contamination gear. The man was so thrilled he bought the whole trilogy. I did assiduous research for the Windscale details, and I hope this reader finds the result interesting at a personal level.

I can’t remember how many people came by to tell me that they’d read and enjoyed my books and to enquire about the next one. And there was the usual number of people who told me how many others they had lent their copies to. Sometimes books lent out don’t come back, and there’s good business in replacing them, which is fine.

There’s a special reason why I enjoy the Gosforth Show in particular. In the second book of the trilogy ‘Forgiven’ a key scene is set at this show, in 1947, which marks another backward step in the relationship between my flawed and sometimes thoughtless heroine Jessie and her daughter-in-law Maggie. Writing it made me wince and smile simultaneously. As one of my readers has told me, ‘That Jessie, sometimes I could slap her.’

By the end of the day I’d sold more books than I would sell through other outlets in a month or more. It meant standing on damp grass in a draughty tent for five hours, but so what. When you self-publish that’s part of what you sign up for, and I’m lucky that I enjoy it so much. On Saturday September 3rd I’m doing a workshop at the Borderlines Book Festival in Carlisle. It’s called ‘Successful Self-Publishing’ which might be on the optimistic side, but it’s a better title than ‘How to try really hard to self publish without losing money’. I’m learning all the time and it’ll be fun to share, and to find out how other people are managing too. If you Google ‘Borderlines Carlisle’ you’ll find the details among the workshops at Tullie House, on Sept. 5th at 2-5pm.

Large dairy farms often employ people to help with milking and the care of the herd, but during the outbreak restrictions were introduced that made it impossible for dairy farm workers to work normally, going home after work and coming back the next day. This particular farm asked a family friend from Liverpool to come and stay on the farm for the duration to help them, and the young man had no experience of farming life. He reacted to the everyday routines of the farm as you or I might, noticing things that the farmers took for granted, asking naive questions, making mistakes through lack of experience. In literary terms, this character’s function is somewhere between the Greek chorus and the gravediggers in Hamlet, and more emotionally detached than the farmers themselves as the outbreak spread ever closer. In a crime story, as this will be, the ‘stranger’ can also be a useful source of tension and mystery. Let’s see how it all turns out.

Large dairy farms often employ people to help with milking and the care of the herd, but during the outbreak restrictions were introduced that made it impossible for dairy farm workers to work normally, going home after work and coming back the next day. This particular farm asked a family friend from Liverpool to come and stay on the farm for the duration to help them, and the young man had no experience of farming life. He reacted to the everyday routines of the farm as you or I might, noticing things that the farmers took for granted, asking naive questions, making mistakes through lack of experience. In literary terms, this character’s function is somewhere between the Greek chorus and the gravediggers in Hamlet, and more emotionally detached than the farmers themselves as the outbreak spread ever closer. In a crime story, as this will be, the ‘stranger’ can also be a useful source of tension and mystery. Let’s see how it all turns out.

? If it’s within the past year or two, that could be a problem. In 2014, when I was looking for a title for my novel set in and around the Windscale reactor fire in Cumbria in 1957, the title ‘Fallout’ was an obvious choice, and I really wanted it. Just three months before we went to print another novel appeared with that title, published in the UK, and I had to make the choice. In the end I decided to go ahead, but I’ve noticed that since publication we’ve had two copies returned – which I guess arose from the confusion over the title. I still think I made the right decision, though, and the cover is pretty special too. ‘Garish’ someone called it, but at least it gets noticed.

? If it’s within the past year or two, that could be a problem. In 2014, when I was looking for a title for my novel set in and around the Windscale reactor fire in Cumbria in 1957, the title ‘Fallout’ was an obvious choice, and I really wanted it. Just three months before we went to print another novel appeared with that title, published in the UK, and I had to make the choice. In the end I decided to go ahead, but I’ve noticed that since publication we’ve had two copies returned – which I guess arose from the confusion over the title. I still think I made the right decision, though, and the cover is pretty special too. ‘Garish’ someone called it, but at least it gets noticed.

Recent Comments