by Ruth Sutton | Apr 18, 2020 | Burning Secrets, character, crime fiction, Cruel Tide, Cumbria, fact-based fiction, historical fiction, plotting, research, stories, West Cumbria

It seems like eons ago that I decided to update my website, in another era, when we could go shopping, and see friends, and even have a holiday. The latter stages of working with my steadfast ‘helper’ Russell – bless him! – have been via Zoom, which was great as we could share what was on our laptops. Then we had issues with the Bookshop to work out and finally, finally, the whole thing was ready.

Russell picked out some of my past blog posts just to get us started, but now I’m writing a new post for the first time in a long time, to celebrate the new site. For a week or two I’ve been wondering how I could write a new post without reference to my novel writing which seemed to be on hold, paralysed by the sudden availability of time that I wasn’t prepared for. But as the first weeks of self-isolation have passed my mind has slowly turned to the idea of a new novel, and worked through the thicket of decisions about setting. The location is a given, it’ll be West Cumbria like all my other stories, but the question has been – When?

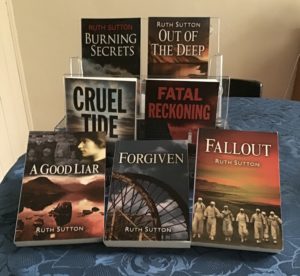

As some of you may know, I started some years ago with a trilogy set over twenty years, from 1937 to 1957. Then I turned to crime fiction and began with ‘Cruel Tide’ set in 1969, followed by its sequel two years later in 1971. After that I faced a quandary: I wanted to focus on a female CID officer in the Cumbrian force, but then discovered that there were no females above the rank of DC until the late 1990s, so the 1980s were passed over and my sixth novel ‘Burning Secrets’ was set against the dystopian background of the Foot and Mouth outbreak of 2001, followed by the seventh ‘Out of the Deep’ later that same year.

So, now what? Earlier this year I was favouring writing a ‘prequel’ to the original trilogy, set in and around Barrow-in-Furness just before World War One. That would have necessitated a fair amount of research and primary documentation accessible through the Records Office, but that door closed – literally – as the current lockdown began. So I needed a writing project that could use research already done, filling in some of the blanks in the chronology of the series so far.

For some time I’d wanted to look at the 1980s, a time when policing was changing almost beyond recognition. During that decade the Police and Criminal Evidence Act was passed, DNA testing was first used in criminal prosecution, the Crown Prosecution Service began, and developments in computing revolutionised the gathering and collation of data. There would be many police officers who welcomed and embraced all these changes, but there would be others – inevitably – who hankered for the old ways of doing police business.

Tension and disagreements make for good stories, and the backdrop of the 1980s provided other useful national and local flash points. The Miners’ Strike of 1984, for example, did not affect Cumbria directly as the few hundred miners left in the county voted to keep working, but that decision also would bring with it the kinds of tension that a good story will thrive on. So after much wandering around, I think I’ve decided on the year, and can build my cast of characters accordingly, some of them already established in the first two crime novels, and others in the early stages of careers that we’ve already witnessed in the 2001 novels.

This sounds like a logical thought process, which was far from the case, but now at last I have an idea that might float, and a place to start. New website, new story – a fresh start all round.

by admin | Oct 19, 2018 | Authenticity, crime fiction, genre, planning, plotting, research, self-publishing, setting, Uncategorized

How easy  it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers.

it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers.

Editors, designers, proof-readers, printers, they’re all provided, and you the author need not worry about any of it. You’ll have to respond to the editor, and approve the cover, and check the final proofs, but most of the responsibility rests with your publishers. For this they get well rewarded if your book sells well, and carry the deficit if it doesn’t.

If your books sell really well, and in doing so keep the entire operation afloat, your publisher will be very keen to support you in any way they can. If like me you write what is mysteriously called ‘genre fiction’ the publisher will want you to keep those books rolling out, one a year if you can manage it, and if that means providing the expert help you need to keep going, so be it.

A good crime writer knows the importance of research and getting the facts right.  Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do?

Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do?

The trick is to gather around you a team of people to help, so that you can spend your time assembling all this information into an engaging story. You’ll need someone to advise about policing, and someone else as the forensics expert. Other aspects of criminality might need expert input too – gang behaviours, money laundering, drug smuggling, whatever. The aristocracy of the crime writing world, Ann Cleeves, Peter Robinson, Val McDermid and the like, will have all the necessary experts ready to assist, presumably paid for out of the hefty profits the publishers will make from the resulting best-sellers. The self-made artisans of the writing world, however, don’t have such support, unless we find and pay for it ourselves. At which point I ask myself, what price expertise?

I’m used to finding the production experts I need – editor, ‘type-setter’, cover designer, proof-reader, printer, – and paying each of them the agreed fee up front, before the book goes on sale. But I’m now I find myself wanting expert help of a different kind even as the book is being written. Unlike many crime writers who have had careers in the law, or the probation service, or the police, I have no professional background and expertise to draw upon. I choose a setting, and characters, and a story, but I still need expert input to get the crime details right, and sometimes the story itself will hinge around the procedural details.

I’m really grateful to the retired DI who advises me, and who wants nothing more for his help than cups of tea and acknowledgement in the book, but I’ve struggled to find someone on the forensics issues. Textbooks and online sites are available, but they have to relate to the time period: for a story set in 2001 I scoured the booklists looking for a a text written before that time, to make sure that it was pertinent to my setting. It’s interesting to do it all myself but it takes so much time, and trying to complete a book a year is just too much.

The latest move is to cast my net wider in looking for expert help that won’t cost me more than I can afford.  My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

As much as the expertise, what I’m most looking forward to is the chance to talk to someone who is interested in what I’m doing. Writing as a self-published author, and living in a wonderful rural location, it can be a lonely life. Maybe this could be the start of a collaboration that will be fun as well as fruitful.

by admin | Jul 9, 2018 | accident, slow writing,, character, creativity, crime fiction, editing, planning, plotting, research, setting, stories, Uncategorized, writing

The last blog post was all about slowing down, taking things easy, enjoying the unusually lovely weather, and yet here I am, only a few days later, reflecting on my default attitude to life which seems to be ‘Life is short, don’t hang around, make decisions, get things done, move on.’

I’m pretty sure I know why this is so: most of my immediate family members have died prematurely. Father went out to work one day when he was 45, died at work and never came home. Mother declined into Alzheimers in her mid-60s and died four years later. One of my older sisters died at 37 and another at 65. I think it was Dad’s sudden disappearance when I was nine that had the most profound effect. Suddenly my certainty about the future was fractured. If he could go without warning and with such effect, anything could happen, and the future could not be relied upon. If there was something I wanted to do, or to become, don’t wait. Just go for it. It may not be planned to perfection, but that’s OK.

Sometimes you need to ‘Ready, fire, aim’. If you think and dither around for too long it becomes ‘Ready, ready, ready.’

I was listening this morning to Michael Ondaatje,  author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

Probably not! I’m 70 now, and enjoying every aspect of my life. I have many things to do and to learn, not just my writing. Worse, as soon as I start thinking about writing another book I start planning deadlines and put time pressure on myself. The urge to write too quickly is so strong that my first response now is to avoid that pressure altogether by not writing at all. There must be another way, surely, somewhere between Ondatjee’s caution and my usual recklessness.

The next step could be, consciously and deliberately, to dawdle. Just mess around for a while. I have some characters I’d like to play with, and I have a setting – it has to be Cumbria, nowhere else provides the same inspiration. Now what I need is a story, a real character-driven story, not just a series of twists and turns choreographed by some formulaic notion of ‘tension’. The story needs to intrigue me, and move me. The central character might be a police person but it’s not going to be a ‘police procedural’ or a forensic puzzle, both of which in the modern era require tedious technical research.

Maybe I should abandon even the pretence of ‘crime fiction’ and just tell a story about a person and a crisis. Above all, I need to drift and learn to use the first draft as a mere sketch. Only then will I know whether I’ve got something worth spending time on. ‘Ready, fire, aim.’

by admin | Jan 20, 2018 | editing, planning, plotting, research, selling, thinking, Uncategorized

Yesterday morning a strange feeling came over me, a sense of loss and uncertainty, a long way from the delight and celebration I’d anticipated at ‘The End’, the final words of the new novel. In the final week, for six days straight from first thing in the morning u ntil it was dark I’d tapped away furiously, stopping only to gaze at the wall while I found a way through a barrier. The concentration was intense: it spilled over into those times when I wasn’t sitting at the laptop, and unfortunately haunted the night too. I would sleep for a couple of hours and then wake with dialogue or a plot twist in my head.The only way to break its hold on my mind was to play Solitaire on the ipad, which meant more screens, more eye strain and was probably not conducive to getting back to sleep. When I’m writing, the usual habit of reading before sleep doesn’t seem to work.

ntil it was dark I’d tapped away furiously, stopping only to gaze at the wall while I found a way through a barrier. The concentration was intense: it spilled over into those times when I wasn’t sitting at the laptop, and unfortunately haunted the night too. I would sleep for a couple of hours and then wake with dialogue or a plot twist in my head.The only way to break its hold on my mind was to play Solitaire on the ipad, which meant more screens, more eye strain and was probably not conducive to getting back to sleep. When I’m writing, the usual habit of reading before sleep doesn’t seem to work.

When ”The End’ finally came it took me by surprise, and more surprising was that I felt so flat. Maybe it had happened before, but if it did I’d forgotten. Living alone, there was no one to turn to in triumph. Friends are very patient, but listening to someone banging on about the details of a fictional conversation or the way out of a plot puzzle is enough to make your eyes roll back.

I was ahead of schedule, but worried that I’d been too driven by the deadline and should have taken more time. I’d resolved a big plotting problem, but it still felt too cerebral, too subtle, not enough action. I’m working with a new editor and chose her for her experience and ‘hard-nosed’ straight-forwardness, but I don’t know how she’ll react to the first draft of mine she’s ever seen. Worry, worry, worry.

And of course, the ever-present question: why do I put myself through this? I’ve retired from ‘work’ and should be pleasing myself, sauntering through the days, going on little jaunts, planning big jaunts, seeing people, having fun. And instead of that I’m spending most of time on research, planning, writing, re-writing, and worrying.

I tell myself that the rewards are worth the painful gestation and birth. It’s undoubtedly true that you have to keep writing if you want to maintain people’s interest in your work and the sales that go with it. Every new books boosts sales of the previous ones. If you want press interest or access to speaking at book events and festivals you have to have a new book to showcase.

I tell myself that the rewards are worth the painful gestation and birth. It’s undoubtedly true that you have to keep writing if you want to maintain people’s interest in your work and the sales that go with it. Every new books boosts sales of the previous ones. If you want press interest or access to speaking at book events and festivals you have to have a new book to showcase.

If all goes well, the new book should be out in June, and then what? I have a choice: pack it in and have an easy life, or keep going and endure the lows as well as the highs, all over again.

by admin | Jan 7, 2018 | cover, feedback, genre, planning, Publishing, readers, research, self-publishing, Uncategorized, writing

WARNING People write books about this: one blog post can cover only the bare bones

We can split the process of going from story in your head to books available to readers (in whatever form) into three parts. As a self-published writer, you’re on your own: whatever help you need will need to be found, by you, and paid for if necessary. You can do it all yourself if you wish, and save the money, but the finished product could be an embarrassment, and most of us would want to avoid that, unless – like the current US President – you think you’re a genius and therefore infallible.

Part 1 is about getting the story out in first draft form, and will apply whether you have a publishing deal or not.  You will need an idea, a setting – time and place – some characters who interest you and a story that hopefully will engage potential readers. Whether you plan in detail or not is your choice, and you also decide when you will write, where, for how long, alone or in collaboration with others. Personally, I do plan – although the plan changes all the time. I write at home, out in the shed if the weather’s good, upstairs if it’s not too cold, and downstairs if I need more warmth. I research and plan for several months before starting the first draft and then I try to write chapters in the order in which they’ll be read. Once I’m writing, the first draft emerges pretty quickly.

You will need an idea, a setting – time and place – some characters who interest you and a story that hopefully will engage potential readers. Whether you plan in detail or not is your choice, and you also decide when you will write, where, for how long, alone or in collaboration with others. Personally, I do plan – although the plan changes all the time. I write at home, out in the shed if the weather’s good, upstairs if it’s not too cold, and downstairs if I need more warmth. I research and plan for several months before starting the first draft and then I try to write chapters in the order in which they’ll be read. Once I’m writing, the first draft emerges pretty quickly.

Part 2 is about everything that has to happen between the completion of a first draft and the final manuscript being ‘published’ in either paperback or ebook format.

a) story edit. You may feel you don’t need this if you’ve had feedback about the story as you go along.  This is where the details of the story are checked to see if they hang together. Does the chronology work? Are there inconsistencies of any kind? Does every chapter/scene add to the story? Does the plot develop in a way that keeps the reader going? I like to get feedback from someone who’s not encountered the story before, beyond the initial outline. The person needs to understand how stories work, to be clear in their judgement and able to provide a critique which is helpful without being bossy – it’s your story, after all.

This is where the details of the story are checked to see if they hang together. Does the chronology work? Are there inconsistencies of any kind? Does every chapter/scene add to the story? Does the plot develop in a way that keeps the reader going? I like to get feedback from someone who’s not encountered the story before, beyond the initial outline. The person needs to understand how stories work, to be clear in their judgement and able to provide a critique which is helpful without being bossy – it’s your story, after all.

b) next draft, use the notes from a) to improve the quality. Any manuscript will improve with careful editing, but beware of ‘over-writing’ which makes the text feel too elaborate and heavy.

c) back to the editor for ‘line-editing’, with a focus now on the grammatical and other details, to clear up any infelicitous phrasing, poor punctuation etc. Lots of errors will be picked up. Don’t assume that corrections can be made at the proof-reading stage, where you will have very little room for correction. The final edited manuscript must be as good as you can get it.

d) the text has to be laid out in the form that will appear on the page. With or without expert help, you have to decide – depending on whether it’s on the page or the screen -on the font, the page size and layout, chapter headings, placing of page numbers, all sorts of visual details. I never know what to call this stage – probably ‘design’ is the best word to use. A professional book designer can make a book look beautiful – but it’s one more person to be paid.

e) cover design. Here again it depends how much you want to spend, and how visible the cover will actually be. On the Kindle store the dimensions will be small with not much room for detail. The cover of a paperback can be more dense. Either way, the cover is the first indication to the reader (and the bookseller/browser too) of what the book might be about. Different genres have different styles. If you want to get ideas, go to a bookshop or library and look for covers that seem to work, analyse why they do, and use those insights in either designing your own cover or briefing someone else to do it.

f) preparing and checking proofs. This is the very final check before your book is published. Once it’s out there, it’s too late to change anything.  One of my books slipped through this stage with insufficient attention and I have regretted it ever since – far too many tiny errors that a fast reader wouldn’t even notice but a slow/picky reader did and will. There’s always a kind person out there who will send you the unbearable list of mistakes. The best way to get the proofs properly checked is to have them read by someone with a professional and very picky approach and who has never encountered your story before, at all, ever. Some of the best proof-readers read from back page to front to avoid getting so involved with the story that their reading speed picks up and mistakes are missed. We need proof-readers, even if we might not want to spend the evening with them.

One of my books slipped through this stage with insufficient attention and I have regretted it ever since – far too many tiny errors that a fast reader wouldn’t even notice but a slow/picky reader did and will. There’s always a kind person out there who will send you the unbearable list of mistakes. The best way to get the proofs properly checked is to have them read by someone with a professional and very picky approach and who has never encountered your story before, at all, ever. Some of the best proof-readers read from back page to front to avoid getting so involved with the story that their reading speed picks up and mistakes are missed. We need proof-readers, even if we might not want to spend the evening with them.

I know this is all pretty basic, but I’m constantly surprised by questions from people who don’t know what self-publishing entails but think it might be right for them.

You’ll recall I said there are three stages. If you think that Stage Three is about sitting back and watching the money roll in you are gravely mistaken. Stage Three is about getting people to pay their money to read your book, and that doesn’t happen unless you do something to make it happen. More on that later.

by admin | Oct 18, 2017 | character, creativity, genre, plot devices, plotting, point of view, research, setting, stories, structure, Uncategorized

Every writer has a different approach to planning their work. Some claim not to plan at all: they just have an idea, start with a blank page and ‘Chapter 1’ and go from there. How they do it, and make it work, I have no idea.

The rest of us will need to do more merely thinking ahead. There’s so much to juggle, setting – both time and place, research where necessary and how much of it to use, and – probably the most important – characters and their backstories. Maybe some people can hold all that in their heads or a few scraps of paper, but I can’t.

Of course there are apps and software that you can use, to organise everything and make it easier to access and use. I have tried to use Scrivener, more than once, but having started my writing in the old days using just a Word document for each chapter, that’s the only way that seems to work for me. Although I started writing fiction only a few years ago I’d spent my professional life before that writing documents, papers, and books too using Word and the habit was too deeply ingrained to change.

My first novel was a planning disaster, with failed attempts to develop a complex story without a clear consistent idea of chronology and how the different threads of the story would weave together. It took two years to salvage the chaotic first draft and I never want to go through that again. Then, on a wet Saturday in Winnipeg, I heard an ad. on the radio for a talk at the central library by Andrew Pyper, an author from Toronto. I braved the rain and walked into town from Osborne Village and wondered whether it would be worth it. It was, definitely.

attempts to develop a complex story without a clear consistent idea of chronology and how the different threads of the story would weave together. It took two years to salvage the chaotic first draft and I never want to go through that again. Then, on a wet Saturday in Winnipeg, I heard an ad. on the radio for a talk at the central library by Andrew Pyper, an author from Toronto. I braved the rain and walked into town from Osborne Village and wondered whether it would be worth it. It was, definitely.

When Pyper talked us through the way he puts the key events, people, twists, conversations, climaxes, scenes on separate sheets and then pins them up on a wall, it was all so obvious. Think of the big boards they have in police investigations, with photos and names and events, arrows, links, questions and ideas, and you’ve got an image of a plan for a novel. It’s a form of simultaneous visual display: you can see links and connections that don’t present themselves from a ‘list’. This may have something to do with the way our minds work: I happen to be a visual thinker, and quite random sometimes, so this form of display will probably work well for me.

This way of working is useful for developing the structure of the novel too.  If you’ve got the key points of the story on separate cards you can move them around, arrange them into a time line, into chapters and then into ‘Acts’, either three or five. If you’re not sure what that’s about, Google it and you’ll find endless advice, diagrams, and so on. It’s the way most movies are constructed, and has seeped into the structures of others genres too.

If you’ve got the key points of the story on separate cards you can move them around, arrange them into a time line, into chapters and then into ‘Acts’, either three or five. If you’re not sure what that’s about, Google it and you’ll find endless advice, diagrams, and so on. It’s the way most movies are constructed, and has seeped into the structures of others genres too.

I did warn you I’m a random thinker! So you won’t be surprised that I want to go backwards for a moment, to the very inception of the story, way before you get to the storyboard stage. Something has to spark you off. Pyper calls this the ‘what if’ stage: you read a piece in a newspaper and ask yourself, ‘What if that happened in the last century, not now?’ or ‘What if the key person was young and female not old and male?’ or ‘What if there was a storm and all phone and email communication was lost?’ or ‘What if DNA hadn’t been discovered when the story happened?’ or ‘What if you write this in the first person, not the third person?’

The ‘what if’s’ are endless. I recall that Pyper asked members of the audience to sum up their story in twenty five words and tell us. He then took ‘what if’ questions from the audience, and what a creative five minutes that was. You could see sparks flying all round the room. I asked the inevitable question: ‘Has Pyper ever written all this down, so we could go over it again?’ No, he never had. So all you’ve got is what I’m conveying here, although I’m sure other authors operate in much the same way and have written books about their writing process that I haven’t read.

So, you have an idea, twist it around with ‘what if’s’ to make it more interesting, start thinking about characters – their appearance, clothes, gait, speech, passions and fears, then weave them together and place them in a time and a place, and see what happens.

When you’ve got this far, go to the next stage, the ‘storyboard’ and the structure, and when you start to write, start at the beginning. I know it’s tempting to start on a big scene that’s set somewhere in the middle or right at the end, but you could be wasting an awful lot of time. I know, I did.

Just a caveat about planning too tightly…no matter what you plan on the page, and how detailed may be your vision of an ending, don’t assume that it will all work out exactly as you envisaged. When you get into the detail of your writing things will occur to you for the first time. Your characters may say something that throws the scene into a different direction, and from that all sorts of unanticipated things may happen. My advice is to plan tight for only three or four chapters ahead as you write and leave the future more flexible. If you’ve spent too much time on the long term plot you may want to hang on to it when the best decision would be to change it.

If you’re a teacher, you’ll recognise this dilemma: you have a plan for the week or the semester but learning is less predictable than teaching. For the sake of learning, the plan needs to change, so change it.

it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers.

it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers. Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do?

Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do? My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that? ntil it was dark I’d tapped away furiously, stopping only to gaze at the wall while I found a way through a barrier. The concentration was intense: it spilled over into those times when I wasn’t sitting at the laptop, and unfortunately haunted the night too. I would sleep for a couple of hours and then wake with dialogue or a plot twist in my head.The only way to break its hold on my mind was to play Solitaire on the ipad, which meant more screens, more eye strain and was probably not conducive to getting back to sleep. When I’m writing, the usual habit of reading before sleep doesn’t seem to work.

ntil it was dark I’d tapped away furiously, stopping only to gaze at the wall while I found a way through a barrier. The concentration was intense: it spilled over into those times when I wasn’t sitting at the laptop, and unfortunately haunted the night too. I would sleep for a couple of hours and then wake with dialogue or a plot twist in my head.The only way to break its hold on my mind was to play Solitaire on the ipad, which meant more screens, more eye strain and was probably not conducive to getting back to sleep. When I’m writing, the usual habit of reading before sleep doesn’t seem to work. I tell myself that the rewards are worth the painful gestation and birth. It’s undoubtedly true that you have to keep writing if you want to maintain people’s interest in your work and the sales that go with it. Every new books boosts sales of the previous ones. If you want press interest or access to speaking at book events and festivals you have to have a new book to showcase.

I tell myself that the rewards are worth the painful gestation and birth. It’s undoubtedly true that you have to keep writing if you want to maintain people’s interest in your work and the sales that go with it. Every new books boosts sales of the previous ones. If you want press interest or access to speaking at book events and festivals you have to have a new book to showcase. You will need an idea, a setting – time and place – some characters who interest you and a story that hopefully will engage potential readers. Whether you plan in detail or not is your choice, and you also decide when you will write, where, for how long, alone or in collaboration with others. Personally, I do plan – although the plan changes all the time. I write at home, out in the shed if the weather’s good, upstairs if it’s not too cold, and downstairs if I need more warmth. I research and plan for several months before starting the first draft and then I try to write chapters in the order in which they’ll be read. Once I’m writing, the first draft emerges pretty quickly.

You will need an idea, a setting – time and place – some characters who interest you and a story that hopefully will engage potential readers. Whether you plan in detail or not is your choice, and you also decide when you will write, where, for how long, alone or in collaboration with others. Personally, I do plan – although the plan changes all the time. I write at home, out in the shed if the weather’s good, upstairs if it’s not too cold, and downstairs if I need more warmth. I research and plan for several months before starting the first draft and then I try to write chapters in the order in which they’ll be read. Once I’m writing, the first draft emerges pretty quickly. This is where the details of the story are checked to see if they hang together. Does the chronology work? Are there inconsistencies of any kind? Does every chapter/scene add to the story? Does the plot develop in a way that keeps the reader going? I like to get feedback from someone who’s not encountered the story before, beyond the initial outline. The person needs to understand how stories work, to be clear in their judgement and able to provide a critique which is helpful without being bossy – it’s your story, after all.

This is where the details of the story are checked to see if they hang together. Does the chronology work? Are there inconsistencies of any kind? Does every chapter/scene add to the story? Does the plot develop in a way that keeps the reader going? I like to get feedback from someone who’s not encountered the story before, beyond the initial outline. The person needs to understand how stories work, to be clear in their judgement and able to provide a critique which is helpful without being bossy – it’s your story, after all. One of my books slipped through this stage with insufficient attention and I have regretted it ever since – far too many tiny errors that a fast reader wouldn’t even notice but a slow/picky reader did and will. There’s always a kind person out there who will send you the unbearable list of mistakes. The best way to get the proofs properly checked is to have them read by someone with a professional and very picky approach and who has never encountered your story before, at all, ever. Some of the best proof-readers read from back page to front to avoid getting so involved with the story that their reading speed picks up and mistakes are missed. We need proof-readers, even if we might not want to spend the evening with them.

One of my books slipped through this stage with insufficient attention and I have regretted it ever since – far too many tiny errors that a fast reader wouldn’t even notice but a slow/picky reader did and will. There’s always a kind person out there who will send you the unbearable list of mistakes. The best way to get the proofs properly checked is to have them read by someone with a professional and very picky approach and who has never encountered your story before, at all, ever. Some of the best proof-readers read from back page to front to avoid getting so involved with the story that their reading speed picks up and mistakes are missed. We need proof-readers, even if we might not want to spend the evening with them. attempts to develop a complex story without a clear consistent idea of chronology and how the different threads of the story would weave together. It took two years to salvage the chaotic first draft and I never want to go through that again. Then, on a wet Saturday in Winnipeg, I heard an ad. on the radio for a talk at the central library by Andrew Pyper, an author from Toronto. I braved the rain and walked into town from Osborne Village and wondered whether it would be worth it. It was, definitely.

attempts to develop a complex story without a clear consistent idea of chronology and how the different threads of the story would weave together. It took two years to salvage the chaotic first draft and I never want to go through that again. Then, on a wet Saturday in Winnipeg, I heard an ad. on the radio for a talk at the central library by Andrew Pyper, an author from Toronto. I braved the rain and walked into town from Osborne Village and wondered whether it would be worth it. It was, definitely. If you’ve got the key points of the story on separate cards you can move them around, arrange them into a time line, into chapters and then into ‘Acts’, either three or five. If you’re not sure what that’s about, Google it and you’ll find endless advice, diagrams, and so on. It’s the way most movies are constructed, and has seeped into the structures of others genres too.

If you’ve got the key points of the story on separate cards you can move them around, arrange them into a time line, into chapters and then into ‘Acts’, either three or five. If you’re not sure what that’s about, Google it and you’ll find endless advice, diagrams, and so on. It’s the way most movies are constructed, and has seeped into the structures of others genres too.

Recent Comments