by Ruth Sutton | Oct 10, 2020 | book covers, crime fiction, Cumbria, historical fiction, Lake District, Publishing, readers, setting, Uncategorized, West Cumbria

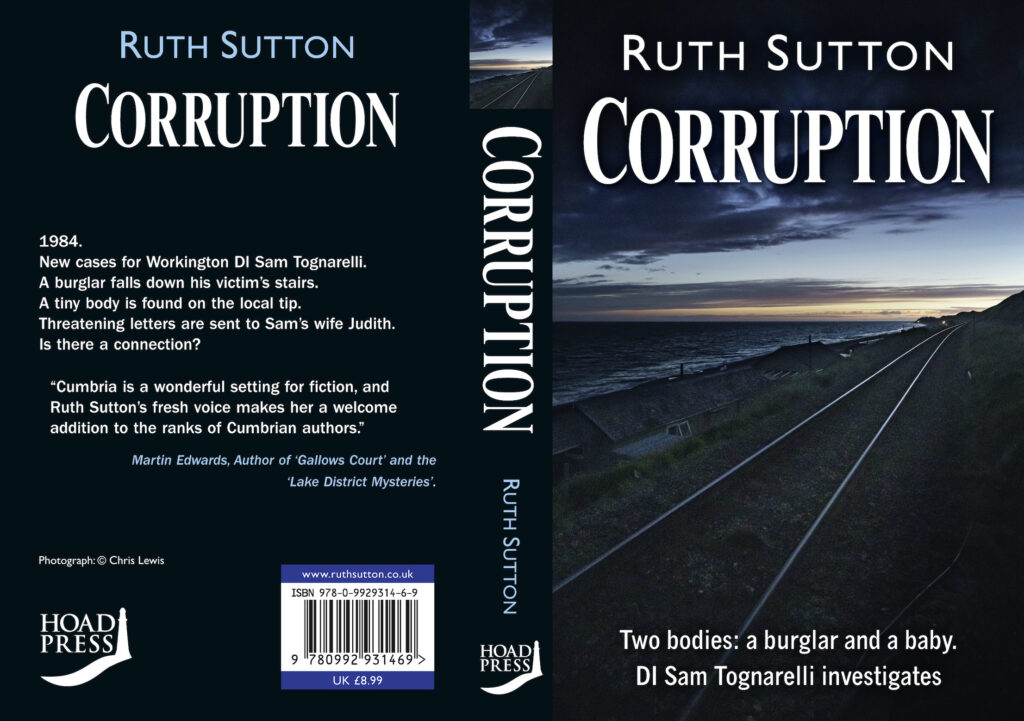

Here it is – the cover of the new book. It’s due out on November 6th 2020, a child of the lockdown, and a good yarn. I’ll add it to my Paypal-linked website bookshop before publication day, and the Kindle version will be available after Christmas. The ISBN number is 978-0-9929314-6-9 if you want to buy it through your local bookshop. Tell your friends!

by admin | May 1, 2018 | A Good Liar, Cumbria, ebook, Fahrenheit Press, Forgiven, Lake District, marketing, Pricing, Publishing, readers, self-publishing, Uncategorized

Well, I put ‘A Good Liar’ on the Kindle free ebook list last week and 115 copies were downloaded over the five days of the offer. At the same time the number of (KENP) pages being read of both ‘A Good Liar’ and ‘Forgiven’, which is the next book in the series, both went up markedly.  There may or may not be a connection. This week I’ve tried another Kindle promotion strategy, putting ‘Forgiven’ into the process where the price progresses from low back to the ‘normal’ of around £4 over four days. No noticeable increase in downloads as yet, but I admit I’ve been too busy to do anything about telling anyone about the promotion. At least there’s some income from this strategy, but it doesn’t look particularly effective so far.

There may or may not be a connection. This week I’ve tried another Kindle promotion strategy, putting ‘Forgiven’ into the process where the price progresses from low back to the ‘normal’ of around £4 over four days. No noticeable increase in downloads as yet, but I admit I’ve been too busy to do anything about telling anyone about the promotion. At least there’s some income from this strategy, but it doesn’t look particularly effective so far.

More news on that next week. In the meantime, I’ve sent the new book ‘Burning Secrets’ to the printers and can do no more with it until the delivery arrives on May 31st. I know I should be more proactive about promotion, but I need a break after the struggle to get all the production stages completed on time and make all the necessary decisions. And I had a big birthday party to organise and then enjoy – which I did, very much.  Loads of people came from away, and it was great to have a steady flow of visitors on the following morning, so we could catch up properly.

Loads of people came from away, and it was great to have a steady flow of visitors on the following morning, so we could catch up properly.

I could have put flyers about my new book on the tables at my party, and made a little speech about it, and had a draw for a free copy, but I just didn’t want to to do that. This was an important personal occasion, and the books are about what I do, not who I am. Does that make sense?

Hitting the big 70 puts things in perspective, and running around pushing people to buy my books isn’t top of my priorities. There are many readers, especially in Cumbria, who enjoy the books and say so, and have been anticipating the new one for some time. I’ll do the usual round of meetings, talks, festivals and radio, and hope that will draw some new readers in too. The ebook and Amazon sales will be picked up by my US distributors Fahrenheit Press and its charismatic MD Chris McVeigh,who knows the book selling business far better than I do. I could do with a similar ‘champion’ here in the UK – someone who loves my work and knows how to promote it – and does so for love, not money. Maybe that’s unrealistic, and lazy!

by admin | Apr 19, 2018 | cover, ebook, promotion, Publishing, readers, self-publishing, Uncategorized

I had an interesting exchange recently with an indie publisher who’s been in the trade for many years and seen it all. This is what he said on the issue of eBook prices. “Things are tough for every indie publisher – readers seem to have decided that the price point for eBooks is 0.99 or free and as you know there are very small margins involved at that level”. Oh yes, the margins are very small indeed.

decided that the price point for eBooks is 0.99 or free and as you know there are very small margins involved at that level”. Oh yes, the margins are very small indeed.

Self-publishing writers like me are attracted to eBooks for all sorts of reasons. The upfront costs are minimal compared with publishing ‘real’ books; you don’t have to decide how many to produce, balancing unit costs and the risk of coping with unsold stock; and there are no issues around storage. Cheap and easy, or so it appears.

But, if you want to produce an ebook to an acceptable standard, you may want help with editing, and proofreading, and the cover. All those need to be paid for, and the costs will far outweigh the cost of conversion to eBook format. And if you want people to buy your book, in whatever format, you will need to publicise and promote it. Any potential reader first needs to know that your book exists, and believe that they want to spend some money on it. Promotion takes effort and energy and can be frustrating, as you realise that ‘professional’ reviews are unachievable, the market is saturated, local media don’t care that much, and advertising is expensive.

The promotional strategy that takes least effort is simply to lower the price, and here’s where the problem starts that all of us are currently facing. If a sufficient proportion authors are prepared to sell their work for £1 or $1, or even give it away to manipulate the ‘best-seller’ lists, how can we then persuade readers to pay a proper price, for a product that represents many many hours or work? It makes no sense to under-price, and thereby under-value, a book. It cheapens the writing process, and makes me – for one – feel like a mug.

If selling for these ludicrous prices were a rarity, and a temporary way to attract buyers, fair enough. But the ‘bargain’ price has now become the ‘standard’ price and the value of our work as writers appears to be permanently  debased.

debased.

I would love to increase my ebook sales, but right now I’m simply not prepared to reduce the price to less than a cup of tea. Am I being foolish? Maybe, but I value my self-respect.

by admin | Apr 4, 2018 | crime fiction, feedback, Publishing, self-publishing, Uncategorized, writing

Of course, the question is facile: it’s not as black and white as that. So let’s pick apart the proof-reading stage of the publishing process, just to see what it contributes and where problems can arise.

First off, doing without proof-reading is a mistake. Nothing irritates a reader and or embarrasses a writer more than published text containing missing words, incorrect or unclosed speech marks, upper case/lower case mistakes, or whatever the obvious transgression might be.  Having said that, something seems to depend on the reader. While some readers spot everything, and usually tell you so, others seem not to notice at all.

Having said that, something seems to depend on the reader. While some readers spot everything, and usually tell you so, others seem not to notice at all.

As an ex-educator with a very picky grammar school education, I’m unbearably fussy about punctuation, or I least I thought I was until a recent experience with a professional proof-reader. My ‘rules’ seem to be based on what I’d learned at school and not updated since, and I was unprepared for the technical approach to writing that my proof-reader friend was keen on. And from what I read about current approaches to ‘grammar’ in English primary schools, it looks like today’s children are getting a bellyful of these ‘rules’ which are then tested: enough to put them off writing confidently for a long time.

I have had a very unfortunate experience with proof-reading, which I’m keen not to repeat. My first three books fared well, or relatively well, with very few errors being spotted during that first nervous check when they came back from the printers. Maybe we got complacent, even sloppy. When the fourth book arrived, something had gone badly wrong. I spotted one or two mistakes in a casual flick through, but then the careful readers’ feedback started. At first it was a general complaint about the number of errors, and then after a routine library talk a woman handed me a list of the errors she had spotted and kindly written out for me. My stomach turned when I glanced at the list of shame. For days I could hardly bear to look at it. Then one morning after a miserable night worrying about it, I sat in bed with the list, a copy of the book and a highlighter pen and marked up every single one. It took a while. In my distress I managed to get highlighter on my duvet covet and it has proved impossible to get rid of, reminding me of the miserable business every time the duvet cover appears on my bed.

It took a while. In my distress I managed to get highlighter on my duvet covet and it has proved impossible to get rid of, reminding me of the miserable business every time the duvet cover appears on my bed.

The colleagues who had helped me with the errant book’s publication were duly informed and were as puzzled as me. How had this happened? We still can’t explain: it was as if the penultimate uncorrected proofs had been sent for printing by mistake. The ebook version of the book was corrected immediately, which was a relief, but I couldn’t afford to scrap the printed paperbacks and redo them. Mercifully, two years on, the stocks of the first edition are almost exhausted now and we can correct the mistakes before the reprint.

No need to convince me of the essential need for proof-reading. The conventions of the written form need to be visible in the text, to make the reader’s life bearable. But…are all these conventions set in stone? Some renowned authors have chosen to ignore them completely, but we can’t all be James Joyce.

Here’s my question: does the style and intensity of proof-reading vary according to genre? What’s acceptable – and required – in an academic paper maybe just too much for a work of fiction. And what’s appropriate to ‘literary fiction’, where writing style is the first concern, may feel wrong in a plot-driven crime story. Even within a story, the level of technical accuracy in a descriptive paragraph will and should be quite different than in dialogue, where people simply don’t speak in full balanced sentences with semi-colons and sub-clauses and all the rest.

Here’s my advice: when you’re working with a new proof-reader, ask for a few sample pages before he/she starts work in earnest. Be prepared for a discussion about the level of correction that could be deemed essential and what is a matter of choice and style. It’s your book, and you call the shots, but obviously you’ll listen to advice from a professionally trained person, even if sometimes you choose to ignore it. I’m sure that some proof-readers yearn to be editors even after the editing stage is officially over, but that could lead to all sorts of confusion and frustration. You – the author – may have to arbitrate and mediate. It’s your name on the cover, and you carry the can.

Back to the original question: can proof-reading flatten language? Yes, potentially it can, by applying ‘rules’ too heavily and inappropriately. If that’s not what you want, make sure you discuss the process with your proof-reader and find an acceptable compromise. “She who pays the piper calls the tune.”

by admin | Mar 13, 2018 | promotion, Publishing, Uncategorized

I saw an advert today for a ‘writing conference’, but actually it was an event designed solely to give writers access to a group of agents, for whom the writers were expected to ‘perform’, aka ‘pitching’. For this experience the writers would travel to the venue and pay a considerable fee. Could this be entitled a ‘writing conference’? It was about seeking approval from an agent, nothing more. Who are these arbiters of quality, and where does their power come from?

I saw an advert today for a ‘writing conference’, but actually it was an event designed solely to give writers access to a group of agents, for whom the writers were expected to ‘perform’, aka ‘pitching’. For this experience the writers would travel to the venue and pay a considerable fee. Could this be entitled a ‘writing conference’? It was about seeking approval from an agent, nothing more. Who are these arbiters of quality, and where does their power come from?

I need to declare an interest: twice in my writing life over the past ten years I have tried to find a agent, and twice the attempt has been fruitless. The second time, as a moderately successful self-published author, I said as much in my ‘pitching’ letter, and in one of the few responses I received I was told that my success so far was really nothing special and that I should be more ‘humble’. Thanks for that. Most of the responses from agents I have gathered over the years have been generic, making no specific reference to my work, which I suspect had not been read.

Sour grapes? Bitterness? Yes, probably. I’ve had a long professional career and don’t relish being ‘judged’ by a group of people whose qualifications for their role are so hard to define or to check. Granted my experience is limited, but the ‘average’ agent appears to be young (ie. younger than my daughter), well-spoken, publicly anodyne, and based in London. All of the agents I have encountered at conferences have been female, but some of the ones I’ve written to have been male, so gender may be immaterial.

I suspect that age may matter in this lottery of who will be of interest to an agent. The agent’s living comes from a percentage of an author’s sales/earnings. If the author has thirty or so years of writing life ahead of them they are a more attractive investment than someone like me who started late. It must also help to be well-connected in writing circles, with a wide reach for promotion purposes. When agents are, as they claim to be, inundated by submissions, the fact that the writer knows someone who knows someone would probably help too. Selecting a very small number from a huge range of applicants must be a nightmare, and any easy selection criteria must be welcome.

A fundamental dilemma of current publishing lurks beneath all these more superficial choice mechanisms. No one in publishing seems to be clear about what they are looking  for. ‘We need new voices’, they cry, but are drawn by the lure of sales to replicate the most recent best-seller. Best-sellers are regularly a surprise, as predictable as a winning lottery ticket. The agent must be risk-averse and a risk-taker simultaneously. No wonder their public statements are often so bland and unhelpful. A regular pronouncement from the agenting group is that they know a good book because they ‘fall in love’ with it, and we all know what an arbitrary process that is, impossible to define or to rationalise.

for. ‘We need new voices’, they cry, but are drawn by the lure of sales to replicate the most recent best-seller. Best-sellers are regularly a surprise, as predictable as a winning lottery ticket. The agent must be risk-averse and a risk-taker simultaneously. No wonder their public statements are often so bland and unhelpful. A regular pronouncement from the agenting group is that they know a good book because they ‘fall in love’ with it, and we all know what an arbitrary process that is, impossible to define or to rationalise.

If the yearned-for book is impossible to describe, perhaps the agent is actually looking for a writer instead? Does he/she really want someone young, photogenic, articulate, ambitious, flexible/malleable? Find a book with some quality – not much better than thousands of others but with a ‘promotable’ author – pour a great deal of money into promotion and hope for the best. We are told that the great majority of published fiction fails to make any money at all: not a great affirmation of the agents’ or publishers’ judgement.

Without an agent, I continue to self-publish, and it’s hard work. I would love someone to take on the responsibility of getting my manuscript into production, although I would be less happy with the paltry royalties. But I’m done with agents. Going to a ‘pitching’ conference seems like buying a very expensive lottery ticket, with similar chances of success.

by admin | Feb 26, 2018 | A Good Liar, agents, book covers, cover, crime fiction, Cruel Tide, promotion, Publishing, Uncategorized

With the ms of the new book with the copy editor, I’m thinking ahead to the upcoming stages of the book’s production. I’ll be using the same cover designer as on the previous five novels, and have a brilliant photo image already bought and paid for: now I’m wondering about the ‘back cover blurb’ so that the designer can get started.

All of which brings me to the business of finding a ‘quote’ ie. a brief endorsement of either the book, or me as the author, taken directly from a credible source who is willing and able to provide a phrase or two and put their name to them. Amazon readers’ reviews don’t cut it, I’m sorry to say. I’ve used ‘quotes’ on only two of my previous books: the first, on the reprint of ‘A Good Liar’, was hardly effusive, but its source was impeccable in Margaret Forster, an icon of the literary world and a famous Cumbrian. She told me when we started to correspond that she didn’t normally do any kind of endorsements, and I was both surprised and delighted when she agreed to this…..

‘Historical background is convincing, and an excellent ending’

‘A thrilling tale of corruption and exploitation’

The second was from William Ryan, a very successful historical fiction writer, for my first crime novel ‘Cruel Tide’. I’d met him on a course and appealed to him directly, not through his editor or agent, and again was very pleased when he agreed. I’ve not managed – until now – to get a ‘quote’ on any of my other books, but that’s not through lack of effort.

There appears to be some unwritten protocols and other barriers that stand in the way. First, it’s very hard to find a way of approaching an author to ask if they would be willing. I’ve recently been reprimanded because the approach wasn’t made indirectly by my editor. If I had an agent, the approach could presumably have been made that way. Authors don’t widely share their email addresses, understandably, and it is not in the interests of an editor, agent or publisher to have their precious ‘client/commodity’ distracted by a gesture of support to another author, especially – horror! – a self-published one.

Secondly, authors who are successful enough that their name counts for something are obviously going to be very busy people. A recent approach to one was rebuffed by a litany of the pressures that the person was currently having to deal with, which meant that there couldn’t possibly be time to glance through a proffered manuscript and offer a few words. I had used the phrase ‘a quick read’, which was been batted back to me as if it denoted a lack of respect.

The third possible reason for my relative lack of success in my efforts has been the suspicion that authors are asked (or expected?) by their agents and/or publishers to offer quotes only to writers from the same ‘stable’ as themselves. Heaps of ‘quotes’ appear routinely in newly published books, inside as well as on covers: presumably the people who provide them have been able to find the time for the ‘quick read’ or whatever it takes to enable a few phrases to be offered for this purpose. There are ‘insiders’ who scratch each others’ backs in this aspect of publishing, and there are ‘outsiders’ like me, and possibly some of you. As a self-publishing author of what is still known as ‘genre fiction’, I’m accustomed to being treated as some kind of low life, but it still rankles occasionally.

In my darker moments I wonder if this reciprocal endorsement accounts for the stellar ‘quotes’ that sometimes appear on the covers of books that are really not that good, or not up to the usual standards of the author. In my even darker moments I wonder how some of the books on the shelves ever got published at all without apparently being subject to a properly critical edit. Could it be that once your name is known and will sell a book on its own, you can get away with mediocrity?

On a more positive note, my latest book will have a quote on the cover from a well-respected writer in the crime fiction business. It will be what’s known as a ‘generic’ quote, speaking to my books as a whole rather than the new one in particular, and the person providing it – for which I’m very grateful – is someone I happen to know a little from sharing a book festival panel. We’d met and talked, and I could approach him directly without offence. I did, asked politely, and he agreed. Hurray.

There may or may not be a connection. This week I’ve tried another Kindle promotion strategy, putting ‘Forgiven’ into the process where the price progresses from low back to the ‘normal’ of around £4 over four days. No noticeable increase in downloads as yet, but I admit I’ve been too busy to do anything about telling anyone about the promotion. At least there’s some income from this strategy, but it doesn’t look particularly effective so far.

There may or may not be a connection. This week I’ve tried another Kindle promotion strategy, putting ‘Forgiven’ into the process where the price progresses from low back to the ‘normal’ of around £4 over four days. No noticeable increase in downloads as yet, but I admit I’ve been too busy to do anything about telling anyone about the promotion. At least there’s some income from this strategy, but it doesn’t look particularly effective so far. Loads of people came from away, and it was great to have a steady flow of visitors on the following morning, so we could catch up properly.

Loads of people came from away, and it was great to have a steady flow of visitors on the following morning, so we could catch up properly. decided that the price point for eBooks is 0.99 or free and as you know there are very small margins involved at that level”. Oh yes, the margins are very small indeed.

decided that the price point for eBooks is 0.99 or free and as you know there are very small margins involved at that level”. Oh yes, the margins are very small indeed.

debased.

debased. Having said that, something seems to depend on the reader. While some readers spot everything, and usually tell you so, others seem not to notice at all.

Having said that, something seems to depend on the reader. While some readers spot everything, and usually tell you so, others seem not to notice at all. It took a while. In my distress I managed to get highlighter on my duvet covet and it has proved impossible to get rid of, reminding me of the miserable business every time the duvet cover appears on my bed.

It took a while. In my distress I managed to get highlighter on my duvet covet and it has proved impossible to get rid of, reminding me of the miserable business every time the duvet cover appears on my bed. I saw an advert today for a ‘writing conference’, but actually it was an event designed solely to give writers access to a group of agents, for whom the writers were expected to ‘perform’, aka ‘pitching’. For this experience the writers would travel to the venue and pay a considerable fee. Could this be entitled a ‘writing conference’? It was about seeking approval from an agent, nothing more. Who are these arbiters of quality, and where does their power come from?

I saw an advert today for a ‘writing conference’, but actually it was an event designed solely to give writers access to a group of agents, for whom the writers were expected to ‘perform’, aka ‘pitching’. For this experience the writers would travel to the venue and pay a considerable fee. Could this be entitled a ‘writing conference’? It was about seeking approval from an agent, nothing more. Who are these arbiters of quality, and where does their power come from? for. ‘We need new voices’, they cry, but are drawn by the lure of sales to replicate the most recent best-seller. Best-sellers are regularly a surprise, as predictable as a winning lottery ticket. The agent must be risk-averse and a risk-taker simultaneously. No wonder their public statements are often so bland and unhelpful. A regular pronouncement from the agenting group is that they know a good book because they ‘fall in love’ with it, and we all know what an arbitrary process that is, impossible to define or to rationalise.

for. ‘We need new voices’, they cry, but are drawn by the lure of sales to replicate the most recent best-seller. Best-sellers are regularly a surprise, as predictable as a winning lottery ticket. The agent must be risk-averse and a risk-taker simultaneously. No wonder their public statements are often so bland and unhelpful. A regular pronouncement from the agenting group is that they know a good book because they ‘fall in love’ with it, and we all know what an arbitrary process that is, impossible to define or to rationalise.

Recent Comments