by Ruth Sutton | Apr 18, 2020 | Burning Secrets, character, crime fiction, Cruel Tide, Cumbria, fact-based fiction, historical fiction, plotting, research, stories, West Cumbria

It seems like eons ago that I decided to update my website, in another era, when we could go shopping, and see friends, and even have a holiday. The latter stages of working with my steadfast ‘helper’ Russell – bless him! – have been via Zoom, which was great as we could share what was on our laptops. Then we had issues with the Bookshop to work out and finally, finally, the whole thing was ready.

Russell picked out some of my past blog posts just to get us started, but now I’m writing a new post for the first time in a long time, to celebrate the new site. For a week or two I’ve been wondering how I could write a new post without reference to my novel writing which seemed to be on hold, paralysed by the sudden availability of time that I wasn’t prepared for. But as the first weeks of self-isolation have passed my mind has slowly turned to the idea of a new novel, and worked through the thicket of decisions about setting. The location is a given, it’ll be West Cumbria like all my other stories, but the question has been – When?

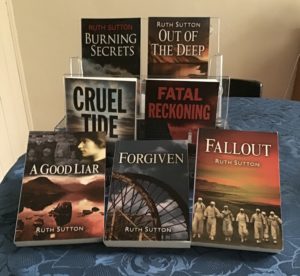

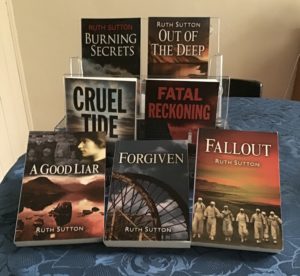

As some of you may know, I started some years ago with a trilogy set over twenty years, from 1937 to 1957. Then I turned to crime fiction and began with ‘Cruel Tide’ set in 1969, followed by its sequel two years later in 1971. After that I faced a quandary: I wanted to focus on a female CID officer in the Cumbrian force, but then discovered that there were no females above the rank of DC until the late 1990s, so the 1980s were passed over and my sixth novel ‘Burning Secrets’ was set against the dystopian background of the Foot and Mouth outbreak of 2001, followed by the seventh ‘Out of the Deep’ later that same year.

So, now what? Earlier this year I was favouring writing a ‘prequel’ to the original trilogy, set in and around Barrow-in-Furness just before World War One. That would have necessitated a fair amount of research and primary documentation accessible through the Records Office, but that door closed – literally – as the current lockdown began. So I needed a writing project that could use research already done, filling in some of the blanks in the chronology of the series so far.

For some time I’d wanted to look at the 1980s, a time when policing was changing almost beyond recognition. During that decade the Police and Criminal Evidence Act was passed, DNA testing was first used in criminal prosecution, the Crown Prosecution Service began, and developments in computing revolutionised the gathering and collation of data. There would be many police officers who welcomed and embraced all these changes, but there would be others – inevitably – who hankered for the old ways of doing police business.

Tension and disagreements make for good stories, and the backdrop of the 1980s provided other useful national and local flash points. The Miners’ Strike of 1984, for example, did not affect Cumbria directly as the few hundred miners left in the county voted to keep working, but that decision also would bring with it the kinds of tension that a good story will thrive on. So after much wandering around, I think I’ve decided on the year, and can build my cast of characters accordingly, some of them already established in the first two crime novels, and others in the early stages of careers that we’ve already witnessed in the 2001 novels.

This sounds like a logical thought process, which was far from the case, but now at last I have an idea that might float, and a place to start. New website, new story – a fresh start all round.

by admin | Feb 26, 2018 | A Good Liar, agents, book covers, cover, crime fiction, Cruel Tide, promotion, Publishing, Uncategorized

With the ms of the new book with the copy editor, I’m thinking ahead to the upcoming stages of the book’s production. I’ll be using the same cover designer as on the previous five novels, and have a brilliant photo image already bought and paid for: now I’m wondering about the ‘back cover blurb’ so that the designer can get started.

All of which brings me to the business of finding a ‘quote’ ie. a brief endorsement of either the book, or me as the author, taken directly from a credible source who is willing and able to provide a phrase or two and put their name to them. Amazon readers’ reviews don’t cut it, I’m sorry to say. I’ve used ‘quotes’ on only two of my previous books: the first, on the reprint of ‘A Good Liar’, was hardly effusive, but its source was impeccable in Margaret Forster, an icon of the literary world and a famous Cumbrian. She told me when we started to correspond that she didn’t normally do any kind of endorsements, and I was both surprised and delighted when she agreed to this…..

‘Historical background is convincing, and an excellent ending’

‘A thrilling tale of corruption and exploitation’

The second was from William Ryan, a very successful historical fiction writer, for my first crime novel ‘Cruel Tide’. I’d met him on a course and appealed to him directly, not through his editor or agent, and again was very pleased when he agreed. I’ve not managed – until now – to get a ‘quote’ on any of my other books, but that’s not through lack of effort.

There appears to be some unwritten protocols and other barriers that stand in the way. First, it’s very hard to find a way of approaching an author to ask if they would be willing. I’ve recently been reprimanded because the approach wasn’t made indirectly by my editor. If I had an agent, the approach could presumably have been made that way. Authors don’t widely share their email addresses, understandably, and it is not in the interests of an editor, agent or publisher to have their precious ‘client/commodity’ distracted by a gesture of support to another author, especially – horror! – a self-published one.

Secondly, authors who are successful enough that their name counts for something are obviously going to be very busy people. A recent approach to one was rebuffed by a litany of the pressures that the person was currently having to deal with, which meant that there couldn’t possibly be time to glance through a proffered manuscript and offer a few words. I had used the phrase ‘a quick read’, which was been batted back to me as if it denoted a lack of respect.

The third possible reason for my relative lack of success in my efforts has been the suspicion that authors are asked (or expected?) by their agents and/or publishers to offer quotes only to writers from the same ‘stable’ as themselves. Heaps of ‘quotes’ appear routinely in newly published books, inside as well as on covers: presumably the people who provide them have been able to find the time for the ‘quick read’ or whatever it takes to enable a few phrases to be offered for this purpose. There are ‘insiders’ who scratch each others’ backs in this aspect of publishing, and there are ‘outsiders’ like me, and possibly some of you. As a self-publishing author of what is still known as ‘genre fiction’, I’m accustomed to being treated as some kind of low life, but it still rankles occasionally.

In my darker moments I wonder if this reciprocal endorsement accounts for the stellar ‘quotes’ that sometimes appear on the covers of books that are really not that good, or not up to the usual standards of the author. In my even darker moments I wonder how some of the books on the shelves ever got published at all without apparently being subject to a properly critical edit. Could it be that once your name is known and will sell a book on its own, you can get away with mediocrity?

On a more positive note, my latest book will have a quote on the cover from a well-respected writer in the crime fiction business. It will be what’s known as a ‘generic’ quote, speaking to my books as a whole rather than the new one in particular, and the person providing it – for which I’m very grateful – is someone I happen to know a little from sharing a book festival panel. We’d met and talked, and I could approach him directly without offence. I did, asked politely, and he agreed. Hurray.

by admin | Feb 18, 2018 | A Good Liar, character, crime fiction, Cruel Tide, Cumbria, Fatal Reckoning, Lake District, plot devices, plotting, self-publishing, setting, stories, structure, Uncategorized, West Cumbria

When I started writing it was really all about setting and character: there was a background story line, but after a while that declined in importance and the interplay of the characters against the West Cumbrian backdrop became the main driving force.

Readers love the Jessie Whelan trilogy for that reason. No one ever comments that the surprises of the plot kept them reading: it was all about what would happen to the people and the interest of the background.

Readers love the Jessie Whelan trilogy for that reason. No one ever comments that the surprises of the plot kept them reading: it was all about what would happen to the people and the interest of the background.

Then I turned to crime fiction, in which the twists and turns of events and revelations have to be managed differently, but in the first two crime books the two leading characters were still centre stage.  ‘Cruel Tide’ and ‘Fatal Reckoning’ are mainly character driven, despite the skull-duggery of the plots. The tension is not so much ‘who dunnit?’, but ‘would the wrong doers be brought to justice?’ There was little in the way of police procedure as neither of the two main characters were senior police people, and the police were more concerned with covering things up than searching for evidence.

‘Cruel Tide’ and ‘Fatal Reckoning’ are mainly character driven, despite the skull-duggery of the plots. The tension is not so much ‘who dunnit?’, but ‘would the wrong doers be brought to justice?’ There was little in the way of police procedure as neither of the two main characters were senior police people, and the police were more concerned with covering things up than searching for evidence.

In the latest book, set in 2001 when everything about policing had changed, police behaviour and procedures are more central. The setting – the disastrous Foot and Mouth epidemic – is also vital, and now I wonder whether the delineation of character is as strong as before. As I re-write and ‘polish’ the question bothers me. In terms of ‘genre’ is this book quite different than the previous ones, and if it is, does that matter? It’s a good story, with enough twists and turns to keep things going. The body count is low – but that’s OK. I’m increasingly tired of dramas that need death after nasty death to sustain the reader’s engagement. After a while, whatever the professed authenticity of the setting, too many crime stories turn out like ‘Death in Paradise’ or ‘Midsomer Murders’. Or is that what happens when crime is adapted for TV? Is it ‘episodic’ presentation that causes the structure of the story to change? Surely what matters is not how many bodies are discovered, or even how they died, but why: what drives someone to attack another? Motive, opportunity, means, in that order. Or are we so jaded that we demand ever more violence?

My final final deadline for the current manuscript is within a day or two. Once the damn thing goes away to the editor I will celebrate for a few days before I have to think about it again. If I had a ‘publisher’ I might be able to relax a little for the next few months while the book makes it way to publication, but when you self-publish every aspect of what happens has to be organised and monitored by yourself. It’s exhausting! As my next big birthday approaches, I’m wondering – again – how much longer I want to carry on. I still have a list of things I enjoy and want to do – sewing, drawing, singing, keeping fit – all of which take time and commitment. The curse of writing is that it seems to squeeze out everything else. I have to give this dilemma some serious thought.

by admin | Mar 19, 2017 | crime fiction, Cruel Tide, Fatal Reckoning, genre, Uncategorized, violence

A year or so ago, it seemed as if the psychological thriller was destined to overtake most other sub-genres of crime fiction. There’ll always be a market for ‘cosy crime’, but the best-seller thrillers were at the other end of the spectrum, featuring graphic violence and sadism, much of which was either directed against or perpetrated by women, and written by women too. Highly improbable twists and turns were the order of the day, and the final climax was required to be sickeningly bloody.

the psychological thriller was destined to overtake most other sub-genres of crime fiction. There’ll always be a market for ‘cosy crime’, but the best-seller thrillers were at the other end of the spectrum, featuring graphic violence and sadism, much of which was either directed against or perpetrated by women, and written by women too. Highly improbable twists and turns were the order of the day, and the final climax was required to be sickeningly bloody.

As an aspiring crime fiction writer I was depressed by this trend. I found the books very hard to read, couldn’t contemplate writing that way, and was therefore apparently condemned to be ‘unfashionable’. Was this just squeamishness or cowardice on my part? No, it was a choice, and I chose not to go that way. My two crime books ‘Cruel Tide’ and ‘Fatal Reckoning’ were strong on setting and character, but seemed to fall between two stools – harmless ‘who-dunnits’ on the one hand, and miserable misogyny on the other. I was heartened when Fahrenheit Press agreed to p ublish my crime novels both as ebooks and POD, but I was less interested in writing further crime fiction if I couldn’t resolve my dilemma about the style.

ublish my crime novels both as ebooks and POD, but I was less interested in writing further crime fiction if I couldn’t resolve my dilemma about the style.

Discussing my future writing ideas recently with a well-connected London-based ‘commissioning editor’ I was surprised and pleased when she offered the view that the trend for violent thrillers was waning, nudged away by a renewed interest in rural rather than metropolitan settings and a gentler view of life, which would in turn produce a different style of crime fiction.

And in recent reports from the London Book Fair, similar views have emerged there too. Maybe it is felt, as I have felt myself, that excessive violence verges on the pornographic and has reached its limits as a popular genre. If this is true, I for one am delighted.

by admin | Feb 28, 2017 | crime fiction, Cruel Tide, Fatal Reckoning, historic child abuse enquiry, historical fiction, Morecambe Bay, research, Uncategorized

Whenever I talk to local audiences about the two crime books, Cruel Tide and Fatal Reckoning, I explain that the institutions where the abuse of children occurred were not on the Morecambe Bay coast of Furness as is portrayed in the stories, but elsewhere. I also explain why I ‘anonymised’ the communities, to hide their identity. One of the challenges of writing local fiction is that communities don’t relish being named as places where bad people do – or did – bad things.

Just this week I’ve been reminded of another challenge: having done so much research about your potential subject matter, how much can you actually use without incurring the critical response – ‘Excuse me, your research is showing.’ The trick is to use only a fraction of the information you have, just enough detail to conjure up the authentic feel of setting or story without boring or overwhelming the reader who wants the plot to move on.

Here’s a case in point. While I was investigating institutional child abuse and how it was covered up in the 1960s and 1970s, I discovered the extent of ‘child emigration’ to the old ‘colonies’ during the post-war years, and the horrific experiences of some of those children. In particular I read about a boy’s home in Western Australia called Bindoon, which was run by Catholic priests. Hundreds of boys were sent there and subject to appalling physical and sexual abuse, which was either not known about by both English and Australian authorities or was discounted or covered up to save them the problem of sorting it out.

Hundreds of boys were sent there and subject to appalling physical and sexual abuse, which was either not known about by both English and Australian authorities or was discounted or covered up to save them the problem of sorting it out.

In my novel Cruel Tide, a mysterious character appears who seems to have spent much of his life in Australia, and has returned to search for his younger brother who has also ended up in care. Without spoiling the plot, let’s say he meets a tragic end. In all but the final draft of the novel, as he lies dying he says one word ‘Bindoon.’ It’s a strange word, and I really wanted readers to wonder about it, and follow later attempts to find out what it meant, or even check it out themselves. My editor wasn’t sure. The word was new to her too. ‘Is it too distracting?’ she asked. ‘Is it necessary?’ In a sense, it was distracting and even unnecessary, but I held out for its inclusion until the very last draft, when I folded, succumbed to advice and took it out. If you want to see the context, read Chapter 21 of Cruel Tide. Better still, read the whole book.

This week, there it is in the top news stories: ‘Bindoon’, as the enquiry into historic child abuse begins its work in London, with a focus on the abuse suffered by the child migrants in Australia. How I wish I’d left the reference in place, as a testament to those nameless boys and what they went through.

by admin | Jan 15, 2017 | Authenticity, Cruel Tide, fact-based fiction, Fatal Reckoning, genre, Lake District, landscape, Morecambe Bay, readers, research, Sellafield, Uncategorized, West Cumbria

It was a wild and snowy night, with a full moon wierdly visible through the snow, as I drove to a readers’ group meeting at Grange-over-Sands library on Thursday and spoke to the hardy souls who turned up. Talking about the new book ‘Fatal Reckoning’  without giving away most of the plot was a challenge, so I relied on questions to pick up what my ‘audience’ wanted to discuss. ‘You obviously like to use specific local settings,‘ said one, ‘but what about people who nothing about the place? Doesn’t that specificity make them feel excluded and put them off?’

without giving away most of the plot was a challenge, so I relied on questions to pick up what my ‘audience’ wanted to discuss. ‘You obviously like to use specific local settings,‘ said one, ‘but what about people who nothing about the place? Doesn’t that specificity make them feel excluded and put them off?’

It’s a good question, and one that’s been on my mind for a while. Many of my most enthusiastic readers are local to the region of West Cumbria that I love and have used as the setting for all my books so far. The area has everything a story backdrop should have – interest, historical depth, variety, beauty and even controversy, in the local nuclear industry based around Sellafield. Occasionally I have to anonymise the community I’m writing about, but mostly the place names and the details are precise, and that’s what many of my readers enjoy. They haven’t seen references to their own home turf in novels before, and it’s great fun to recall them in your mind’s eye as you read.

But there’ll be many more readers – I hope – for whom the area is unknown and the specific references immaterial. Honestly, I don’t think this detracts from their reading pleasure. All of us read about places we don’t know, and accept the author’s word about what the settings look like. Too much description is a drag, but we appreciate enough detail to picture the scene, whether the setting is authentic or not. We enjoy finding out more about the setting of a good book: evocations of Ann Cleeve’s Shetland or Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh add immeasurably to the reading experience.

For me, setting is important on a number of levels. For all readers it provides the visual context of the story, adding colour and depth to the ‘events’. Sometimes, setting is so crucial that it becomes almost a character in itself.  In my first crime novel ‘Cruel Tide’ the vast mudflats of Morecambe Bay and its sneaking tides are central to the plot. This can be achieved whether or not the reader knows the area herself. Local knowledge is not and should not be essential, but it adds another layer of enjoyment for some readers. This is especially so when the locality has previously been neglected in fiction, which I feel West Cumbria has been. Cumbria has been celebrated by many writers and poets, but not the west of the county, where the mountains meet the Irish Sea and seams of coal stretch further west under the waves. Coal and ore mining have gone, steel and iron works have closed, ship building has been replaced by nuclear submarines and commercial fishing is a shadow of past prominence, but the fascination of this coastal area continues and cries out to be shared. My next writing project may be different in characters and genre, but I’ve no doubt the setting will be the same, and hope it will be appreciated whether the readers are familiar with it or not.

In my first crime novel ‘Cruel Tide’ the vast mudflats of Morecambe Bay and its sneaking tides are central to the plot. This can be achieved whether or not the reader knows the area herself. Local knowledge is not and should not be essential, but it adds another layer of enjoyment for some readers. This is especially so when the locality has previously been neglected in fiction, which I feel West Cumbria has been. Cumbria has been celebrated by many writers and poets, but not the west of the county, where the mountains meet the Irish Sea and seams of coal stretch further west under the waves. Coal and ore mining have gone, steel and iron works have closed, ship building has been replaced by nuclear submarines and commercial fishing is a shadow of past prominence, but the fascination of this coastal area continues and cries out to be shared. My next writing project may be different in characters and genre, but I’ve no doubt the setting will be the same, and hope it will be appreciated whether the readers are familiar with it or not.

Readers love the Jessie Whelan trilogy for that reason. No one ever comments that the surprises of the plot kept them reading: it was all about what would happen to the people and the interest of the background.

Readers love the Jessie Whelan trilogy for that reason. No one ever comments that the surprises of the plot kept them reading: it was all about what would happen to the people and the interest of the background. ‘Cruel Tide’ and ‘Fatal Reckoning’ are mainly character driven, despite the skull-duggery of the plots. The tension is not so much ‘who dunnit?’, but ‘would the wrong doers be brought to justice?’ There was little in the way of police procedure as neither of the two main characters were senior police people, and the police were more concerned with covering things up than searching for evidence.

‘Cruel Tide’ and ‘Fatal Reckoning’ are mainly character driven, despite the skull-duggery of the plots. The tension is not so much ‘who dunnit?’, but ‘would the wrong doers be brought to justice?’ There was little in the way of police procedure as neither of the two main characters were senior police people, and the police were more concerned with covering things up than searching for evidence.

the psychological thriller was destined to overtake most other sub-genres of crime fiction. There’ll always be a market for ‘cosy crime’, but the best-seller thrillers were at the other end of the spectrum, featuring graphic violence and sadism, much of which was either directed against or perpetrated by women, and written by women too. Highly improbable twists and turns were the order of the day, and the final climax was required to be sickeningly bloody.

the psychological thriller was destined to overtake most other sub-genres of crime fiction. There’ll always be a market for ‘cosy crime’, but the best-seller thrillers were at the other end of the spectrum, featuring graphic violence and sadism, much of which was either directed against or perpetrated by women, and written by women too. Highly improbable twists and turns were the order of the day, and the final climax was required to be sickeningly bloody. ublish my crime novels both as ebooks and POD, but I was less interested in writing further crime fiction if I couldn’t resolve my dilemma about the style.

ublish my crime novels both as ebooks and POD, but I was less interested in writing further crime fiction if I couldn’t resolve my dilemma about the style. Hundreds of boys were sent there and subject to appalling physical and sexual abuse, which was either not known about by both English and Australian authorities or was discounted or covered up to save them the problem of sorting it out.

Hundreds of boys were sent there and subject to appalling physical and sexual abuse, which was either not known about by both English and Australian authorities or was discounted or covered up to save them the problem of sorting it out. without giving away most of the plot was a challenge, so I relied on questions to pick up what my ‘audience’ wanted to discuss. ‘You obviously like to use specific local settings,‘ said one, ‘but what about people who nothing about the place? Doesn’t that specificity make them feel excluded and put them off?’

without giving away most of the plot was a challenge, so I relied on questions to pick up what my ‘audience’ wanted to discuss. ‘You obviously like to use specific local settings,‘ said one, ‘but what about people who nothing about the place? Doesn’t that specificity make them feel excluded and put them off?’

Recent Comments