by Ruth Sutton | Oct 10, 2020 | book covers, crime fiction, Cumbria, historical fiction, Lake District, Publishing, readers, setting, Uncategorized, West Cumbria

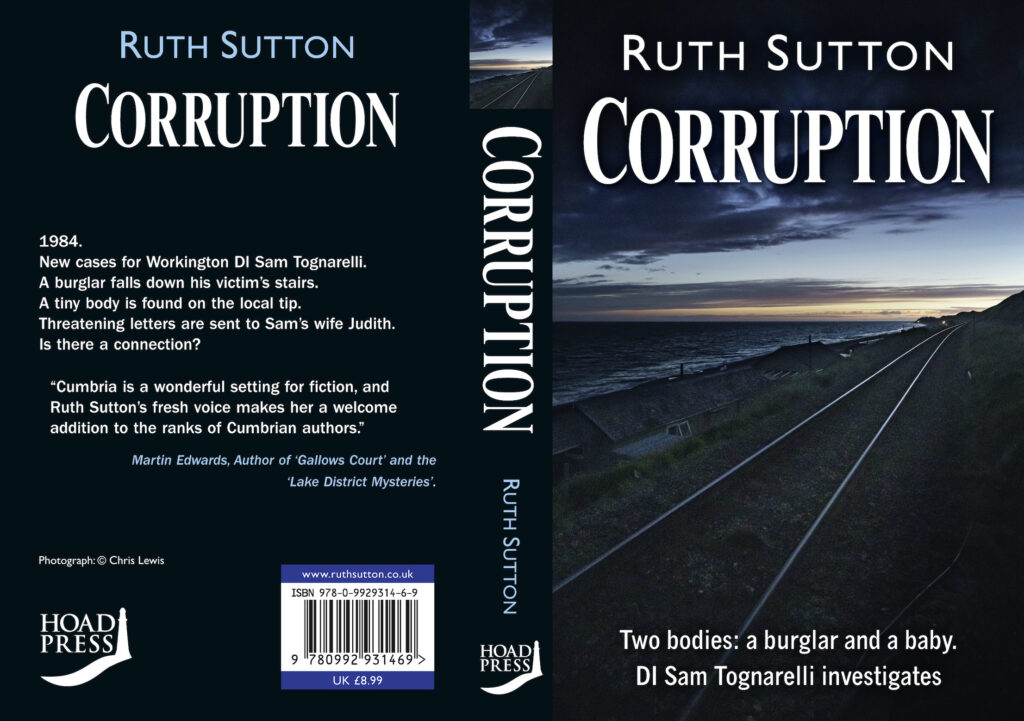

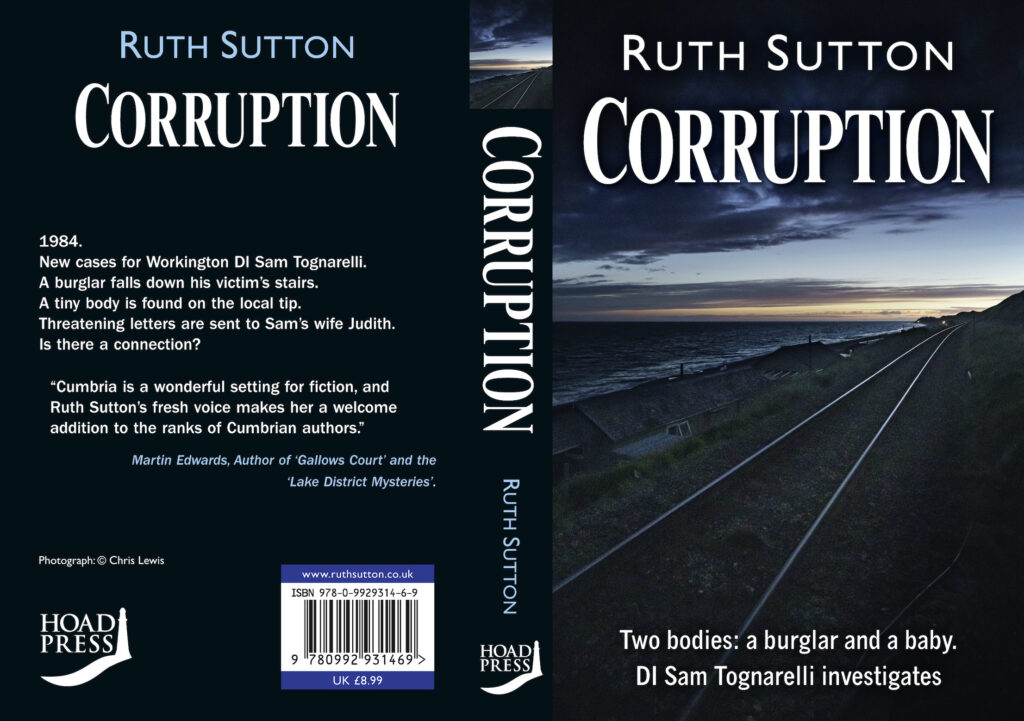

Here it is – the cover of the new book. It’s due out on November 6th 2020, a child of the lockdown, and a good yarn. I’ll add it to my Paypal-linked website bookshop before publication day, and the Kindle version will be available after Christmas. The ISBN number is 978-0-9929314-6-9 if you want to buy it through your local bookshop. Tell your friends!

by admin | Jan 26, 2016 | feedback, on-line learning, Uncategorized, writing workshops

Late again this week with my regular blog post, mainly because much of my screen time has been taken up with a new on-line course, and it’s that experience I’ve been thinking about. I was attracted to it in the first place because it was so much easier and cheaper than schlepping down to London for something similar, finding a place to stay, dealing with a large group whose demands on the tutors always seem more pressing than mine – you know the story.

But cheaper things are often not worth the little you pay for them, so a week or two into it, what are my feelings so far? It’s a first for me, and I wasn’t sure at all. But so far, it’s been OK. It does what any good learning experience should do, make you think about what you’re doing by exposing you to alternatives, providing feedback which is useful as long as it’s specific, and encouraging you to change things and be more adventurous. The course, by the way, is called ‘An Introduction to Crime Writing’ and is with the Professional Writers Academy. The tutor is Tom Bromley, and the visiting ‘mentor’ is Sarah Hilary, a familiar name given her success with ‘Someone Else’s Skin’. Her book is one of those that we’ll be reading and discussing with her as a group exercise.

Other than that, the work is spread over four weeks and provides a succession of structured exercises: first week on ‘settings’, second on ‘developing character’, and so on. For each section we have some contrasting examples to look at and critique, and then a piece of our own to write using what we’ve learned, which is posted and critiqued by at least two others in the group.

What’s working so far? First, we were able to see Tom Bromley talking in a podcast in which he explained the course and introduced himself. It’s always useful to see and hear someone you’re dealing with on-line: without that, it’s very difficult to establish any form of relationship, especially when you are trusting that person to provide something worth both your time and your cash. We have audio interviews too with Sarah Hilary, although audio-only is less engaging. Second, the extracts and writing tasks are well-chosen and conducive to learning. In the second section, on Character, we’ve been offered three examples of ‘the detective’ – the genius who has a massive brain and works everything out; the meticulous plodder who just keeps doing the leg work until enough information is forthcoming; the flawed anti-social person who gets there by some bizarre route the rest of us would never consider. I’ve found those differences interesting, and helpful in deciding what kind of behaviour I want from my ‘detecting’ character. Today I’ll tackle the exercise in which we are asked to describe how our chosen ‘detective’ makes and eats his/her breakfast. What a great idea. As well as enriching the setting, both place and time, we can show so much through just watching and recording what happens in the mind’s eye.

Of course when you’re offered examples it’s tempting to mould your character to fit one of these ‘models’. The seduction of ‘genre formulae’ has to be resisted, even against the siren call of the latest block-buster. If a particular approach has worked and sold heaps of copies for someone else, last year, that’s no reason to attempt to replicate it, even though it might be reassuring to an agent. I had an interesting ‘conversation’ with Tom Bromley about ‘Someone Else’s Skin’ and what constitutes ‘success’, which I’ll come back to in a later post.

I’m enjoying the screen contact with some of the group members, although there are fewer of those than I was anticipating. Some have posted a picture and a detailed profile, others have not, although the privacy protections are strong. It’s easier to ‘talk’ to someone if you know where they’ve been and what they look like, isn’t it? We’re all reacting differently to both the extracts and the tasks, which makes for fewer assumptions about what’s ‘good’ or ‘clear’ for a reader, and that’s salutary for a writer.

One potentially unhelpful aspect is the quality of feedback available to any of us from the other participants who look at what we write. Surprisingly, no guidance is offered about what constitutes useful feedback, and how to react to it: it’s just assumed that we all know how to do it, and we don’t. I want to provide and receive specific detail, critical as well as positive. It takes longer to consider and to write, but if feedback is an essential part of the learning we should expect it to be quite rigorous, and some advice about this would be useful.

So far, so good. Compared to some of the writing groups and courses I’ve been on over the years, this is proving relatively useful. When an actual group works well, which involves good leadership as well as the accident of composition, the experience can be more intense than anything you could achieve on-line. But when a group doesn’t work well it can be immensely frustrating. I recall paying a lot of money and travelling many miles for a five day experience that was a model of what shouldn’t happen. It was a group for established writers but with no ‘filters’, so some of the members had no writing experience and had come only for a holiday. The group leaders were also inexperienced and badly prepared. One of them spent most nights drinking noisily with some of the group members. The following morning his apology for not having read our work – one of his duties – was all about what a great night it had been. After one day I absented myself from the group completely and got on with my writing, which I could have done without leaving home. Looking back on what I wrote that week I notice now how dark and violent it was!

by admin | Aug 5, 2014 | crime fiction, historical fiction, structure

I know I should understand this by now, but I don’t. I’ve asked various people ‘What is ‘genre’ and why do we need it?’ and the only answer that I remember, perhaps because of its absurdity – to me at least – is ‘So that the bookseller/librarian will know which shelf to put it on.’ When I went through the tedious and time-wasting process of submitting my work to an agent, I was informed that knowing your genre was crucially important, presumably so that you pestered the right agent, but that too seems to me like a post-facto rationalisation, a curious case of how the tail can wag the dog.

So here I am, trying to play the game, thinking of a move from one genre (‘regional historical women’s commercial fiction’) into another (‘regional historical crime fiction’). I’ve bought and read the Arvon book on writing crime fiction. I went on a course at Crimefest with Ryan and Hall and reviewed it favourably in an earlier post. Now I’m reading ‘The Crime Writer’s Guide to Police Practice and Procedure’ by Michael O’Byrne (published by Robert Hale in 2009). On the first page of Chapter 1 O’Byrne asks the question I’m asking myself: ‘Is it a crime novel or a novel in which a crime occurs?’ He also makes the assumption throughout that the protagonist of a crime novel must be a ‘detective’.

In the novel I’m now trying to plan, the protagonist is not going to be a ‘detective’, except in the sense that he/she is trying to find out ie. ‘detect’ what happened and why. So no Miss Marple, or Morse, or whatever the Nordic noir guys are called. Does that mean that this story is doomed to be ‘a novel in which a crime occurs’ that will leave the bookseller/librarian weeping with indecision? I stamp my foot. I’m the writer: I don’t want my main character to be in the police force, so there. The story will be what is, so get over it.

Most of the advice I have read and heard about writing good stories applies to any story. The 3 Act structure explained by Ryan and Hall works whether or not crime is involved. It’s about gripping the reader and pulling them into a book they can’t put down. You can perceive this structure in Hardy and Austen, who had the good fortune to write before the strictures of genre were so tight. Did Wilkie Collins know he was writing crime fiction? Of course I’m not comparing my own efforts with those greats, but the whole genre thing feels like a game for which everyone else except me knows the rules. As my kids in school used to say when their glaring ignorance came to light, ‘I must have been away that day.’

Recent Comments