by Ruth Sutton | Apr 18, 2020 | Burning Secrets, character, crime fiction, Cruel Tide, Cumbria, fact-based fiction, historical fiction, plotting, research, stories, West Cumbria

It seems like eons ago that I decided to update my website, in another era, when we could go shopping, and see friends, and even have a holiday. The latter stages of working with my steadfast ‘helper’ Russell – bless him! – have been via Zoom, which was great as we could share what was on our laptops. Then we had issues with the Bookshop to work out and finally, finally, the whole thing was ready.

Russell picked out some of my past blog posts just to get us started, but now I’m writing a new post for the first time in a long time, to celebrate the new site. For a week or two I’ve been wondering how I could write a new post without reference to my novel writing which seemed to be on hold, paralysed by the sudden availability of time that I wasn’t prepared for. But as the first weeks of self-isolation have passed my mind has slowly turned to the idea of a new novel, and worked through the thicket of decisions about setting. The location is a given, it’ll be West Cumbria like all my other stories, but the question has been – When?

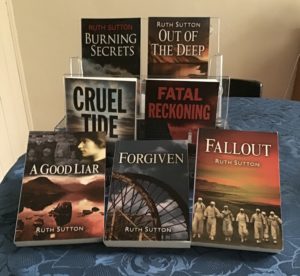

As some of you may know, I started some years ago with a trilogy set over twenty years, from 1937 to 1957. Then I turned to crime fiction and began with ‘Cruel Tide’ set in 1969, followed by its sequel two years later in 1971. After that I faced a quandary: I wanted to focus on a female CID officer in the Cumbrian force, but then discovered that there were no females above the rank of DC until the late 1990s, so the 1980s were passed over and my sixth novel ‘Burning Secrets’ was set against the dystopian background of the Foot and Mouth outbreak of 2001, followed by the seventh ‘Out of the Deep’ later that same year.

So, now what? Earlier this year I was favouring writing a ‘prequel’ to the original trilogy, set in and around Barrow-in-Furness just before World War One. That would have necessitated a fair amount of research and primary documentation accessible through the Records Office, but that door closed – literally – as the current lockdown began. So I needed a writing project that could use research already done, filling in some of the blanks in the chronology of the series so far.

For some time I’d wanted to look at the 1980s, a time when policing was changing almost beyond recognition. During that decade the Police and Criminal Evidence Act was passed, DNA testing was first used in criminal prosecution, the Crown Prosecution Service began, and developments in computing revolutionised the gathering and collation of data. There would be many police officers who welcomed and embraced all these changes, but there would be others – inevitably – who hankered for the old ways of doing police business.

Tension and disagreements make for good stories, and the backdrop of the 1980s provided other useful national and local flash points. The Miners’ Strike of 1984, for example, did not affect Cumbria directly as the few hundred miners left in the county voted to keep working, but that decision also would bring with it the kinds of tension that a good story will thrive on. So after much wandering around, I think I’ve decided on the year, and can build my cast of characters accordingly, some of them already established in the first two crime novels, and others in the early stages of careers that we’ve already witnessed in the 2001 novels.

This sounds like a logical thought process, which was far from the case, but now at last I have an idea that might float, and a place to start. New website, new story – a fresh start all round.

by admin | Jan 2, 2019 | creativity, crime fiction, drafting, planning, plotting, setting, structure, Uncategorized

Over Christmas I read Peter Ackroyd’s excellent biography of Alfred Hitchcock, and was particularly interested in how Hitchcock set about planning his films. He began not with characters, or even with a plot, but with a series of scenes – actions in a setting – and then talked at length with a writer, whose job it was to incorporate these scenes, in any order, into a story.

The film maker’s vision was essentially, and unsurprisingly, ‘filmic’: he saw the scenes in his mind’s eye and then had to unpick and articulate the details in a series of ‘storyboards’. The characters were merely servants of the scenes: it was the writer’s job to get them into these various settings with as much realism and authenticity as possible.

This got me thinking about the new crime novel which is beginning to take shape in my head. I was already aware that the final scene was the first one I’d thought of, and that the planning/plotting process was at least in part about working backwards from the end point. What I began to consider was whether idea that would work repeatedly: could I see the story as a series of key scenes, adding drama through the physical setting as well as by means of dialogue or plot twists. Instead of two characters having a conversation in an office, should they have it on a beach, or in extreme weather, or in a setting that contributed to the tension of the story rather than merely accommodating it?

The other aspect of Hitchcock’s ‘modus operandi’ that I found fascinating was his insistence on developing the details through talking with the writer, not for a few hours, but for days at a time. They would sit together and ask the ‘what if?’ and ‘why?’ and ‘so what?’ and ‘what next?’ and ‘how?’ questions, over and over, until the story evolved in minute visual and aural detail. Neither one of them could have achieved this degree of creativity alone: it had to be through verbal interaction, sparking each other off. The other person who would consistently fulfil this function was of course Alma Reville, Hitchcock’s wife and closest collaborator, an exceptional story teller in her own right.

How does all this square with the image of writing as an isolated activity, with the writer alone in her garrett/office/workroom, emerging only when the masterpiece is complete? Of course it doesn’t. I’m reminded of my conversation with Ann Cleeves about her writing process, which involves several people in the early stages – a forensics expert, a police procedure specialist, and her three agents, all of whom comment on the first draft, asking no doubt the same kinds of questions as those between Hitchcock and his screenwriter.  Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Maybe what every writer needs is a person or a group of people whose sole job is to ask great questions: how many of us can effectively do that for ourselves? And how visual does our planning need to be, as if we are film-makers not just wordsmiths?

by admin | Oct 19, 2018 | Authenticity, crime fiction, genre, planning, plotting, research, self-publishing, setting, Uncategorized

How easy  it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers.

it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers.

Editors, designers, proof-readers, printers, they’re all provided, and you the author need not worry about any of it. You’ll have to respond to the editor, and approve the cover, and check the final proofs, but most of the responsibility rests with your publishers. For this they get well rewarded if your book sells well, and carry the deficit if it doesn’t.

If your books sell really well, and in doing so keep the entire operation afloat, your publisher will be very keen to support you in any way they can. If like me you write what is mysteriously called ‘genre fiction’ the publisher will want you to keep those books rolling out, one a year if you can manage it, and if that means providing the expert help you need to keep going, so be it.

A good crime writer knows the importance of research and getting the facts right.  Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do?

Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do?

The trick is to gather around you a team of people to help, so that you can spend your time assembling all this information into an engaging story. You’ll need someone to advise about policing, and someone else as the forensics expert. Other aspects of criminality might need expert input too – gang behaviours, money laundering, drug smuggling, whatever. The aristocracy of the crime writing world, Ann Cleeves, Peter Robinson, Val McDermid and the like, will have all the necessary experts ready to assist, presumably paid for out of the hefty profits the publishers will make from the resulting best-sellers. The self-made artisans of the writing world, however, don’t have such support, unless we find and pay for it ourselves. At which point I ask myself, what price expertise?

I’m used to finding the production experts I need – editor, ‘type-setter’, cover designer, proof-reader, printer, – and paying each of them the agreed fee up front, before the book goes on sale. But I’m now I find myself wanting expert help of a different kind even as the book is being written. Unlike many crime writers who have had careers in the law, or the probation service, or the police, I have no professional background and expertise to draw upon. I choose a setting, and characters, and a story, but I still need expert input to get the crime details right, and sometimes the story itself will hinge around the procedural details.

I’m really grateful to the retired DI who advises me, and who wants nothing more for his help than cups of tea and acknowledgement in the book, but I’ve struggled to find someone on the forensics issues. Textbooks and online sites are available, but they have to relate to the time period: for a story set in 2001 I scoured the booklists looking for a a text written before that time, to make sure that it was pertinent to my setting. It’s interesting to do it all myself but it takes so much time, and trying to complete a book a year is just too much.

The latest move is to cast my net wider in looking for expert help that won’t cost me more than I can afford.  My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

As much as the expertise, what I’m most looking forward to is the chance to talk to someone who is interested in what I’m doing. Writing as a self-published author, and living in a wonderful rural location, it can be a lonely life. Maybe this could be the start of a collaboration that will be fun as well as fruitful.

by admin | Jul 9, 2018 | accident, slow writing,, character, creativity, crime fiction, editing, planning, plotting, research, setting, stories, Uncategorized, writing

The last blog post was all about slowing down, taking things easy, enjoying the unusually lovely weather, and yet here I am, only a few days later, reflecting on my default attitude to life which seems to be ‘Life is short, don’t hang around, make decisions, get things done, move on.’

I’m pretty sure I know why this is so: most of my immediate family members have died prematurely. Father went out to work one day when he was 45, died at work and never came home. Mother declined into Alzheimers in her mid-60s and died four years later. One of my older sisters died at 37 and another at 65. I think it was Dad’s sudden disappearance when I was nine that had the most profound effect. Suddenly my certainty about the future was fractured. If he could go without warning and with such effect, anything could happen, and the future could not be relied upon. If there was something I wanted to do, or to become, don’t wait. Just go for it. It may not be planned to perfection, but that’s OK.

Sometimes you need to ‘Ready, fire, aim’. If you think and dither around for too long it becomes ‘Ready, ready, ready.’

I was listening this morning to Michael Ondaatje,  author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

Probably not! I’m 70 now, and enjoying every aspect of my life. I have many things to do and to learn, not just my writing. Worse, as soon as I start thinking about writing another book I start planning deadlines and put time pressure on myself. The urge to write too quickly is so strong that my first response now is to avoid that pressure altogether by not writing at all. There must be another way, surely, somewhere between Ondatjee’s caution and my usual recklessness.

The next step could be, consciously and deliberately, to dawdle. Just mess around for a while. I have some characters I’d like to play with, and I have a setting – it has to be Cumbria, nowhere else provides the same inspiration. Now what I need is a story, a real character-driven story, not just a series of twists and turns choreographed by some formulaic notion of ‘tension’. The story needs to intrigue me, and move me. The central character might be a police person but it’s not going to be a ‘police procedural’ or a forensic puzzle, both of which in the modern era require tedious technical research.

Maybe I should abandon even the pretence of ‘crime fiction’ and just tell a story about a person and a crisis. Above all, I need to drift and learn to use the first draft as a mere sketch. Only then will I know whether I’ve got something worth spending time on. ‘Ready, fire, aim.’

by admin | Jun 25, 2018 | author talks, crime fiction, Cumbria, self-publishing, speaking, Uncategorized

As you might have gathered from my last post, and others over the past few months, I’m seriously weighing the positives of writing and self-publishing against the negatives, and there’s no certainty that I will want to continue.

But when I think about giving it all up, one aspect of the process keeps calling me back, and it’s something that many writers would be surprised by: I love talking about my books and my writing, to groups large or small. I love just starting to speak, without notes, and sometimes without a plan or direction, and hearing what comes out of my mouth. It’s different every time, and responds to the nature of the group, their reactions, and their questions. I watch and listen and adjust how I reply. It’s fun and interactive and engaging, as I imagine playing a video game might be, although that’s something I’ve never done.

The people I’m talking to seem to enjoy it too, and tell me so. They’re used to people having a set speech, and my ‘off the cuff’ approach goes down well. Does it sell heaps of books? Who knows? People do buy books from me at these events, and often not just the latest one but earlier ones that I may have mentioned. All my six novels are linked, by setting and by some recurring characters, and some readers really want to start from the beginning, which I applaud.

Who knows? People do buy books from me at these events, and often not just the latest one but earlier ones that I may have mentioned. All my six novels are linked, by setting and by some recurring characters, and some readers really want to start from the beginning, which I applaud.

If I’m talking to a group in a library, I sell less, probably because these people use the library rather than buy their own. If it’s a Women’s Institute audience, the ladies often team up, each buying one of the series and sharing them around – which makes sense for them but isn’t great for sales! People in readers’ groups tend to want their own copies – hurray. However many or few I sell, the money’s welcome and the pile of boxes in my garden room is reduced still further, but that’s not the principal satisfaction.

I really enjoy talking to readers, but if I wasn’t writing, what would be the purpose and rationale for these talks?

If the talks about writing didn’t happen, I’d miss the ‘charge’ I get from doing them. Is that a sufficient reason for keeping going?

Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers. it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers.

it must be to finish a manuscript and just send it off, confident that a small army of people employed by your adoring publisher will immediately step up to do everything necessary to get your masterpiece into the hands of equally adoring readers. Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do?

Whatever setting you choose – contemporary or in the past – the details of police procedures and enquiry methods need to be correct. Forensic science has changed radically over the past thirty years or so, and is progressing all the time, so those details too are very time-specific and all too easy to get wrong. What does the self-publishing writer have to do? My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

My local University website reveals teams of academics specialising in the very areas I want help with. Hallelujah! I scoured the staff lists, looking for the expertise I need, picked some names almost at random, and sent an email explaining what I was looking for and that I couldn’t offer remuneration. My expectations were low, I admit, but were confounded when I got reply from one name almost immediately, taking up my offer to go and talk about what I’m doing and what I need. Result!

author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

author of ‘The English Patient’, talking about his writing approach which involves twenty edits before he commits to print. The first draft is just a sketch, and it goes from there. What patience, I thought to myself. How does he slow down enough to let such snail’s pace iteration happen? Could I ever work like that?

Who knows? People do buy books from me at these events, and often not just the latest one but earlier ones that I may have mentioned. All my six novels are linked, by setting and by some recurring characters, and some readers really want to start from the beginning, which I applaud.

Who knows? People do buy books from me at these events, and often not just the latest one but earlier ones that I may have mentioned. All my six novels are linked, by setting and by some recurring characters, and some readers really want to start from the beginning, which I applaud.

Recent Comments