by Ruth Sutton | Mar 18, 2024 | agents, memory, motivation, structure

My last book was written three years ago, and since then I’ve been unsure whether I had either the motivation or the time to write another. In 2022 I wrote a play because I was asked to do so. The writing, followed by taking the play to the stage, took up the whole of that year. 2023 seemed to be a year of travelling, with one holiday and two trips prompted by the need to see old friends. As I get older I’m aware that I may not be able to see friends overseas as often as I once did, and each time may be the last. I didn’t have enough settled time to start a writing project.

As 2024 began, however, the urge to write emerged from its hiding place and began to bother me, I’ve written in one form or another all my life and I enjoy it. Writing produces a level of concentration that blots out everything else, and feels like really good exercise. If I didn’t have a story waiting to be told, what could I write about? It occurred to me that my grandchildren knew me only as their grandmother, which I have been for the past twenty years or so. My life before they came along is largely unknown to them, and I wanted them to know more about it. Why is that, I wonder? Ego, possibly. Or maybe my wish to inform them is just a front: what I really want is to inform myself, to put my own life into some perspective and see what it looks like on the page.

I’ve seen books and courses on memoir writing but I haven’t checked them to see how such an undertaking should be approached. I decided that so long as I was clear about ‘purpose and audience’, as with any good writing, and kept to that, the form would take care of itself. So I accepted my first decision, that my purpose was to inform my grandchildren and that they were my audience. That has proved useful, for the time being at least. For example, having them as my prospective audience has steered me away from too lengthy and detailed a description of how my partner and I began our relationship, which is probably a blessing.

I’ve called the piece ‘Fragments from a Life’ because it is fragmentary. Some things I remember from decades ago as clearly as the day they happened, while other episodes are only a blur, or have been forgotten all together. As I write, details come back to me, and some of them have been so painful that I’ve had to stop for a while, and they have resurfaced in my dreams. I realise that what cements an incident in my memory is not the factual context but what I was feeling at the time. Emotions create the sharpest memories. One example is a road trip across the USA undertaken in the summer of 1977 with my then husband, my sister, and my young daughter. It included some of the most iconic places and landscapes imaginable, but what I remember most is the misery and exhaustion that enveloped me and blotted out almost everything else. It was probably that misery that has prevented me in the years since from making any effort to remember. I’m sure my daughter, who was nine at the time, will recall far more than I do.

I’ve chosen chronology as the simplest structure, whereas it could conceivably have been arranged in themes – travels, work, family, and so on. Those possible themes have been much entangled, however, which probably says something about my life. Work has been the dominating thread, but being a self-employed person for the majority of my working life means that my working decisions have been personal ones too. I see now that I have regularly put my work needs above family needs, and I have some regrets about that.

So far, the ‘fragments’ amount to nearly 20,000 words, and there’s still a fair bit to cover. I have an agent now, fifteen years after I began writing, and she rubs her hands at the prospect of getting my memoir published, but she will be disappointed as I have no intention of sharing it beyond the family. By the way, the story of how an agent appeared so late on the scene is an interesting one, for another occasion.

For now, I shall plough on and keep editing, editing, editing. I’m enjoying it. Maybe by the end of it I’ll feel more inspired to write another novel, or another play. Who knows?

by Ruth Sutton | May 1, 2020 | drafting, first draft, pace, planning, plotting, structure, Uncategorized

At 7.54am this morning I checked the Tesco online delivery service and to my astonishment, there was a delivery slot available and I got it.  Not only that, I put in a long list of things we needed and checked out. All done within fifteen minutes, booked, paid for and the confirmation email kin the inbox. For some unaccountable reason this minor lockdown triumph filled me with confidence. I’d managed something that had been beyond my reach for weeks.

Not only that, I put in a long list of things we needed and checked out. All done within fifteen minutes, booked, paid for and the confirmation email kin the inbox. For some unaccountable reason this minor lockdown triumph filled me with confidence. I’d managed something that had been beyond my reach for weeks.

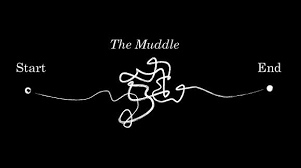

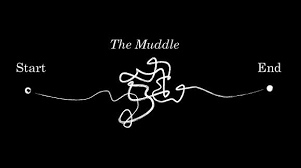

Within hours, the optimistic glow of a obstacle successfully hurdled transferred itself to the outline of a new story I’ve been struggling with. I can do this, I said firmly to myself. If I can scale the Tesco delivery mountain I can sort out the flabby middle of a plot which starts well, and could end well, but flounders around in between.

I can’t be the only one who struggles with a muddle in the middle. This is the stage where the story gets complicated, and possible blind alleys are introduced to tempt the reader but end up confusing the writer instead. It’s all very well starting several hares running, but you have to know roughly where they’re going to end up. I thought I’d done that, but going back to the outline after a bad night I realised that there were plot holes all over the place: hence the feeling of inadequacy that a successful tussle with Tesco seems to have cured.

I can’t be the only one who struggles with a muddle in the middle. This is the stage where the story gets complicated, and possible blind alleys are introduced to tempt the reader but end up confusing the writer instead. It’s all very well starting several hares running, but you have to know roughly where they’re going to end up. I thought I’d done that, but going back to the outline after a bad night I realised that there were plot holes all over the place: hence the feeling of inadequacy that a successful tussle with Tesco seems to have cured.

So now I’m back, unpicking and mending the holes, unmuddling the middle and hopefully adding more life and colour to the story as a whole. The great thing about the current situation is that I can slow down and take my time. No point in having deadlines that just fade into the mist of uncertainty that surrounds us right now. This stage of the writing process will take as long as it takes, and when I’m ready, the first draft will roll out as smooth as a good Malbec.

by admin | May 25, 2019 | character, crime fiction, Cumbria, planning, plotting, point of view, self-publishing, structure, success, Uncategorized, writing

When I’m talking about writing, explaining the balance between plot, character, point of view and setting is a helpful starting point for people who haven’t yet thought about how a novel is developed.  In my West Cumbrian trilogy, the first novels I wrote, setting was the central ingredient. From my research about this amazing place and its history, I began to think about a key character who could carry the story. Having found her, I then had her interact with various other characters. There was some consideration of the plot in the first one, but mostly that developed as I went along, with a fairly quiet conclusion that I felt was an authentic way for the story to end. I didn’t really think about ‘the arc of the narrative’, or how my protagonist might have a ‘journey’.

In my West Cumbrian trilogy, the first novels I wrote, setting was the central ingredient. From my research about this amazing place and its history, I began to think about a key character who could carry the story. Having found her, I then had her interact with various other characters. There was some consideration of the plot in the first one, but mostly that developed as I went along, with a fairly quiet conclusion that I felt was an authentic way for the story to end. I didn’t really think about ‘the arc of the narrative’, or how my protagonist might have a ‘journey’.

At some point in those early years of writing I went to a workshop run by Matthew Hall and William Ryan, who had both come to novel writing from careers as barristers. Part of that workshop, introduced briefly but not fully pursued because of shortage of time, was the idea of the ‘Three Act Structure’ commonly used in films. Hall had spent some time doing film scripts and this was the structure he brought to the novel. I’ve included here a relatively simple representation of this notion: check it on Google and you’ll find various more sophisticated models.

I was intrigued by the relative complexity of the ‘formula’ he presented to us, and read more about it after the workshop, but it always felt to me to be too ‘formulaic’, putting too much emphasis on plot structure, leaving character and setting as servants to the story. Or possibly I just didn’t have the patience to think the idea all the way through. My first interest was always in ‘where’ and ‘who’ rather than ‘how’.

When I moved into crime writing for the fourth book ‘Cruel Tide’, I revisited the thinking about the structure as ‘acts’ that build towards a climax, but still didn’t really reflect the formula in what I produced. Two more crime books followed, and the latest one, as yet untitled, is in production. Reflection on ‘structure’ as the first planning tool had faded almost completely over the intervening years. My books are well-received, within the limitations of that self-publishing brings with it. Many of my readers are Cumbrian, who are as interested as I am in the authenticity of the Cumbrian settings. Because I’m self-published I rarely get any professional reviews, or feedback from other professional writers. I rarely meet professional writers as I live in a remote place, a long way from the normal arteries of the publishing world.

Maybe that was why I suggested to the Kirkgate Arts centre in Cockermouth, an hour north of here in West Cumbria, that we should try to bring some Cumbrian writers together to talk about their work, and I would ‘host’ the event, interviewing the authors and sparking discussion among them. Long story short, the event happened last week was great success: three very different crime writers, all successful, with all sorts of exciting projects in the pipeline.

One of them was Paula Daly, from Windermere.  She writes what she calls ‘domestic noir’, and with such success that two of her novels have been adapted to a 6 part TV drama called ‘Deep Water’, which will air on TV here, starting in August. When the question came up of ‘where do a novelist’s characters come from?’, her answer was very interesting. She starts with structure – just as Matthew Hall had suggested in that workshop years ago. The ‘hero/protagonist’ is the centre of the action and the story tells her story, through various trials and tribulations to a final denouement. The characters all have a function, to support or to impede the hero’s progress, and their roles are planned early on. They are ciphers initially, created to serve the story. Only when the structure is clear are the characters then developed into three-dimensions, with their habits and mannerisms suggested by their preordained function.

She writes what she calls ‘domestic noir’, and with such success that two of her novels have been adapted to a 6 part TV drama called ‘Deep Water’, which will air on TV here, starting in August. When the question came up of ‘where do a novelist’s characters come from?’, her answer was very interesting. She starts with structure – just as Matthew Hall had suggested in that workshop years ago. The ‘hero/protagonist’ is the centre of the action and the story tells her story, through various trials and tribulations to a final denouement. The characters all have a function, to support or to impede the hero’s progress, and their roles are planned early on. They are ciphers initially, created to serve the story. Only when the structure is clear are the characters then developed into three-dimensions, with their habits and mannerisms suggested by their preordained function.

Paula was really clear about this, and I was fascinated by her certainty about the importance of this way of working. Her plotting and planning is done in great detail, she said, and the writing itself is the least enjoyable part of the whole process. It sounded as if the actual writing was almost a chore, an anti-climax after the excitement of developing the narrative. She sees the story in a series of filmic episodes, and it could be written as a screen play rather than continuous prose.

Could I do this. Do I want to? The upside is that stories written this way are almost tailor-made for adaptation into films or TV. The setting is almost immaterial: you use whatever setting is most accessible and attractive to the film-maker.

I’m still thinking, wondering whether this approach is possible for me. Do I have the patience do achieve it, or sufficient ambition to follow the rules? Maybe it’s the idea of ‘rules’ that I have trouble with. I have always been a contrarian and maybe too old, or stubborn, to change my ways.

by admin | Mar 31, 2019 | Authenticity, drafting, planning, plot devices, plotting, stories, structure, Uncategorized

The current fashion in crime fiction seems to be for the writer to visualise the plot of a story in terms of a series of gripping scenes. It’s certainly the way to go if you fancy selling to TV. The drama of these scenes can lie in the characters and their individual or collective crises. Or it can rest in the extraordinary landscape, or with a revelation, or twist in the story, or – possibly – all of these at once. As authors we imagine the details that would make these scenes as engaging as possible, but it’s not easy.

The problem lies in the machinations necessary to get your characters into a particular space at a particular time with a worthwhile revelation to share. The frequent victim of this process is authenticity. What we end up with is a story that just doesn’t makes sense.

All writers try to avoid too many coincidences and accidents in plotting, although one or two are useful if they drive the story forward. Similarly, we treasure dysfunctional characters with flaws, because they can be delightfully unpredictable and prone to mistakes, both of which help with the ‘twists and revelations’ issue. Coincidences, accidents and characters’ poor judgements are all OK up to a point, but if overdone can steer a plot towards improbability. The reader may be asked to ‘suspend their disbelief’ once too often, and if the reader is me the story is dismissed as a ‘fix’.

With the first draft of Book 7 rolling along, I’m right in the middle of this dilemma. I have a number of great scenes in mind, and need them to work without stretching authenticity just that bit too far. I’m looking forward to seeing what my editor will think when she sees the first draft in a month or so.

by admin | Jan 2, 2019 | creativity, crime fiction, drafting, planning, plotting, setting, structure, Uncategorized

Over Christmas I read Peter Ackroyd’s excellent biography of Alfred Hitchcock, and was particularly interested in how Hitchcock set about planning his films. He began not with characters, or even with a plot, but with a series of scenes – actions in a setting – and then talked at length with a writer, whose job it was to incorporate these scenes, in any order, into a story.

The film maker’s vision was essentially, and unsurprisingly, ‘filmic’: he saw the scenes in his mind’s eye and then had to unpick and articulate the details in a series of ‘storyboards’. The characters were merely servants of the scenes: it was the writer’s job to get them into these various settings with as much realism and authenticity as possible.

This got me thinking about the new crime novel which is beginning to take shape in my head. I was already aware that the final scene was the first one I’d thought of, and that the planning/plotting process was at least in part about working backwards from the end point. What I began to consider was whether idea that would work repeatedly: could I see the story as a series of key scenes, adding drama through the physical setting as well as by means of dialogue or plot twists. Instead of two characters having a conversation in an office, should they have it on a beach, or in extreme weather, or in a setting that contributed to the tension of the story rather than merely accommodating it?

The other aspect of Hitchcock’s ‘modus operandi’ that I found fascinating was his insistence on developing the details through talking with the writer, not for a few hours, but for days at a time. They would sit together and ask the ‘what if?’ and ‘why?’ and ‘so what?’ and ‘what next?’ and ‘how?’ questions, over and over, until the story evolved in minute visual and aural detail. Neither one of them could have achieved this degree of creativity alone: it had to be through verbal interaction, sparking each other off. The other person who would consistently fulfil this function was of course Alma Reville, Hitchcock’s wife and closest collaborator, an exceptional story teller in her own right.

How does all this square with the image of writing as an isolated activity, with the writer alone in her garrett/office/workroom, emerging only when the masterpiece is complete? Of course it doesn’t. I’m reminded of my conversation with Ann Cleeves about her writing process, which involves several people in the early stages – a forensics expert, a police procedure specialist, and her three agents, all of whom comment on the first draft, asking no doubt the same kinds of questions as those between Hitchcock and his screenwriter.  Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Maybe what every writer needs is a person or a group of people whose sole job is to ask great questions: how many of us can effectively do that for ourselves? And how visual does our planning need to be, as if we are film-makers not just wordsmiths?

by admin | Aug 31, 2018 | Authenticity, Burning Secrets, crime fiction, Cumbria, drafting, fact-based fiction, genre, planning, plotting, structure, Uncategorized, West Cumbria, writing shed

It’s some weeks since my last post, and I’m still debating whether I want to write another book. It could help if I could pin down why the prospect feels problematic. What is it that fills me with trepidation?

I’ve already accepted that my recollections of the past year have been coloured by my fall down the stairs just over a year ago and all its consequences – temporary immobilisation, pain, frustration, endless physiotherapy. I’m almost back to normal fitness now, but it’s been a long haul.

The content of last book was difficult too. I chose a backdrop – the catastrophic Foot and Mouth outbreak in Cumbria in 2001 – that required very careful research and a balance between authenticity and fear that the ghastliness of it all could overwhelm the ‘front story’. The research was painful, but I live in a farming community and couldn’t get the details wrong.

I was also working with a new editor, which was fine in the end but felt different than the well-worn relationship I’d had earlier. The new editor is very experienced in what makes for successful commercial genre fiction, but sometimes her expectations clashed with my obsession with authenticity. Yes, her ideas for a scene or the ending would be exciting, but if they felt ‘unrealistic’ I couldn’t go along with them. It’s quite a strain to pay someone for their advice and then decide to ignore it. And when I did agree with her, after the first draft, our shared view required a complete re-write of the first quarter of the book, which I didn’t enjoy at all.

For all these reasons, and probably others too, writing the last book rarely flowed easily. I had a deadline, and achieved it, but when ‘Burning Secrets’ finally emerged it didn’t excite me, even when it was clear that readers enjoyed and some think it is my best to date.

Looking back, I think I was so taken up with the research that I didn’t spend long enough on the structure before starting the first draft. So the writing stopped and started, got stuck and had to be rescued, and in the end had to be hammered into submission by some agonised re-thinking of the final scenes. Very stressful. If I could summon the patience and imagination next time to create a better detailed outline, that would definitely help to enhance the writing experience, and avoid painful rewrites further down the line.

Now I have the Arvon writing course to look forward to, which starts on September 10th. I signed up for this particular as the focus seemed to be on structure and plot, which is exactly what I need. I’m going with an open mind to see if help, advice and an undivided focus will clarify the future enough for me to stop writing without regret, or carry on.

In darker moments I think about the boxes of unsold books stored in my writing shed. While I have a new book to promote, sales of all the books tick along nicely. If there’s no new book, will I still be able to sell the backlist? I don’t necessarily need the money, but those boxes could haunt me for a long time.

Not only that, I put in a long list of things we needed and checked out. All done within fifteen minutes, booked, paid for and the confirmation email kin the inbox. For some unaccountable reason this minor lockdown triumph filled me with confidence. I’d managed something that had been beyond my reach for weeks.

Not only that, I put in a long list of things we needed and checked out. All done within fifteen minutes, booked, paid for and the confirmation email kin the inbox. For some unaccountable reason this minor lockdown triumph filled me with confidence. I’d managed something that had been beyond my reach for weeks. I can’t be the only one who struggles with a muddle in the middle. This is the stage where the story gets complicated, and possible blind alleys are introduced to tempt the reader but end up confusing the writer instead. It’s all very well starting several hares running, but you have to know roughly where they’re going to end up. I thought I’d done that, but going back to the outline after a bad night I realised that there were plot holes all over the place: hence the feeling of inadequacy that a successful tussle with Tesco seems to have cured.

I can’t be the only one who struggles with a muddle in the middle. This is the stage where the story gets complicated, and possible blind alleys are introduced to tempt the reader but end up confusing the writer instead. It’s all very well starting several hares running, but you have to know roughly where they’re going to end up. I thought I’d done that, but going back to the outline after a bad night I realised that there were plot holes all over the place: hence the feeling of inadequacy that a successful tussle with Tesco seems to have cured. In my West Cumbrian trilogy, the first novels I wrote, setting was the central ingredient. From my research about this amazing place and its history, I began to think about a key character who could carry the story. Having found her, I then had her interact with various other characters. There was some consideration of the plot in the first one, but mostly that developed as I went along, with a fairly quiet conclusion that I felt was an authentic way for the story to end. I didn’t really think about ‘the arc of the narrative’, or how my protagonist might have a ‘journey’.

In my West Cumbrian trilogy, the first novels I wrote, setting was the central ingredient. From my research about this amazing place and its history, I began to think about a key character who could carry the story. Having found her, I then had her interact with various other characters. There was some consideration of the plot in the first one, but mostly that developed as I went along, with a fairly quiet conclusion that I felt was an authentic way for the story to end. I didn’t really think about ‘the arc of the narrative’, or how my protagonist might have a ‘journey’.

She writes what she calls ‘domestic noir’, and with such success that two of her novels have been adapted to a 6 part TV drama called ‘Deep Water’, which will air on TV here, starting in August. When the question came up of ‘where do a novelist’s characters come from?’, her answer was very interesting. She starts with structure – just as Matthew Hall had suggested in that workshop years ago. The ‘hero/protagonist’ is the centre of the action and the story tells her story, through various trials and tribulations to a final denouement. The characters all have a function, to support or to impede the hero’s progress, and their roles are planned early on. They are ciphers initially, created to serve the story. Only when the structure is clear are the characters then developed into three-dimensions, with their habits and mannerisms suggested by their preordained function.

She writes what she calls ‘domestic noir’, and with such success that two of her novels have been adapted to a 6 part TV drama called ‘Deep Water’, which will air on TV here, starting in August. When the question came up of ‘where do a novelist’s characters come from?’, her answer was very interesting. She starts with structure – just as Matthew Hall had suggested in that workshop years ago. The ‘hero/protagonist’ is the centre of the action and the story tells her story, through various trials and tribulations to a final denouement. The characters all have a function, to support or to impede the hero’s progress, and their roles are planned early on. They are ciphers initially, created to serve the story. Only when the structure is clear are the characters then developed into three-dimensions, with their habits and mannerisms suggested by their preordained function.

Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Ann very generously suggested that her book covers ought to reflect the collective effort of its various collaborators by including all their names, not just hers.

Recent Comments